2 The Legal Framework

Melanie Reed

Learning Objectives

- Describe the legal structure for labour relations in Canada.

- Apply specific laws that impact labour relations in Canada.

- Describe the history and significance of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms for labour relations.

Introduction

It is impossible to study labour relations without studying the legal framework governing labour relations activities in Canada. Union leaders and pioneers of the Canadian labour movement did not originally intend to solve working-class struggles with lawyers and hearings. Still, as you will learn in this and subsequent chapters, the legal system is a part of the modern-day labour relations system. Therefore, it is important that you can describe and apply the laws that impact management and union decisions and activities in Canada.

This chapter will provide an overview of the legal framework and relevant legislation. Subsequent chapters will go into further detail about laws that pertain to specific labour relations topics.

Jurisdiction Matters

Legislation that applies to labour relations in Canada exists in all provinces and territories, as well as specific federal legislation. Whether a workplace follows provincial or federal laws impacting workers and employers depends on jurisdiction. Jurisdiction, in this sense, refers to who has legal responsibility for a particular issue or decision.

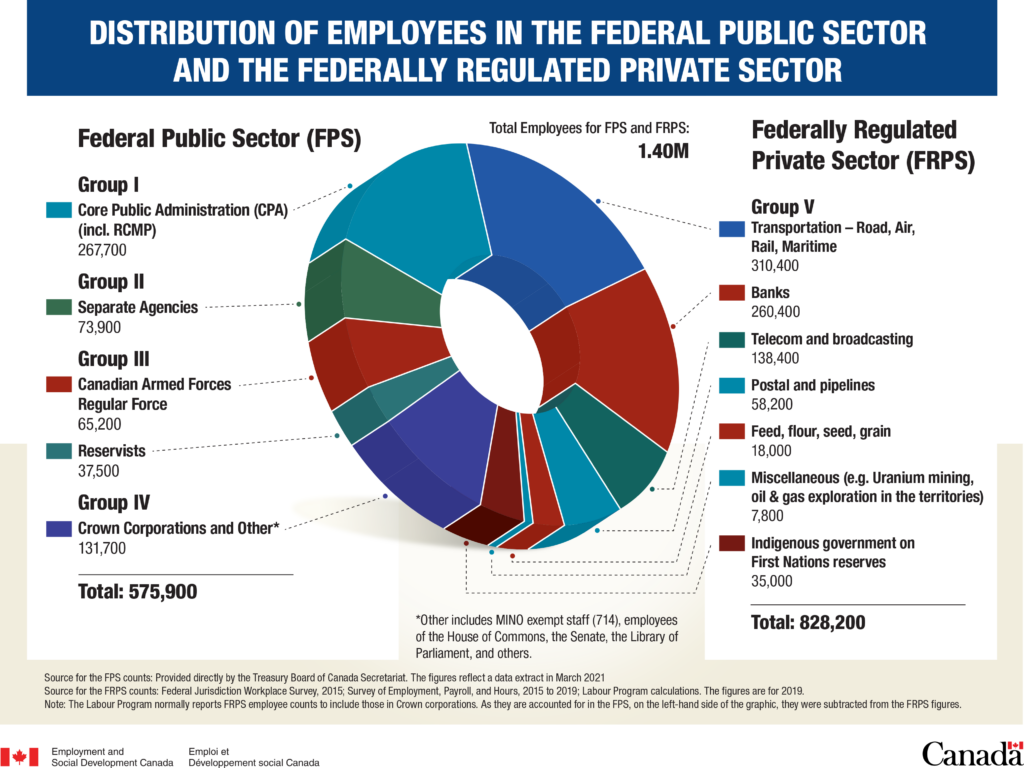

Until the mid-1920s, labour relations concerns were the sole responsibility of the federal government. Following the 1925 Snider v. Toronto Electrical Commission ruling, jurisdiction for labour relations matters was predominantly the responsibility of provincial legislatures. However, federal labour laws still exist and apply to approximately 8% of workers in Canada (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2022a).

You will follow federal labour laws if your workplace is part of the federal public sector or federal private sector. You are part of the federal public sector if you:

- work in federal government administration (e.g. RCMP)

- are a member of the Canadian Armed Forces or a reservist

- work for federal government agencies or federal crown corporations (e.g., Canadian Post Corporation)

Workers belong to the federal private sector if the organization or business operates across provincial borders and, thus, has an interprovincial component. Examples of industries that are part of the federal private sector include:

- banking

- telecommunications

- transportation

- natural resource distribution (i.e. pipelines)

- Indigenous governments on First Nations reserves.

See Figure 2.1 for a breakdown of federally regulated industries and workplaces.

Apply Your Learning

Consider the information you just learned about legal jurisdiction for employment. Answer the following questions to test your understanding. (Answers can be found at the bottom of this page)

- You are a teacher at a private Catholic school in Calgary, AB; which jurisdiction applies to you?

- You are an Air Canada pilot based out of Vancouver, BC; which jurisdiction applies to you?

- You are the head chef at a restaurant in Inuvik, NWT; which jurisdiction applies to you?

- You are a research assistant at York University in Toronto, ON; which jurisdiction applies to you?

Charter of Rights and Freedoms

In 1982, Prime Minister Pierre-Elliott Trudeau and Queen Elizabeth II signed the Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982, which brought to life the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Charter is an important historical document, giving Canada independence by embedding the right to change the constitution without Britain’s permission. The Constitution Act of 1982 replaced the Constitution Act of 1867, also called the British North America Act (McIntosh & Azzi, 2012).

The Charter is not just an important historical artifact for Canadians. It is often called the ‘pre-eminent’ or ‘supreme’ law because it takes precedence over all other laws, regardless of jurisdiction. This means neither the federal nor provincial government can pass a law or regulation denying someone a basic right or freedom contained in the Charter.

However, there are a couple of exceptions to this. The first is spelled out in section 1. It states that “[The Charter] guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society” (Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, 1982, s 7). This means it may be necessary to certain limit rights and freedoms to protect other rights and freedoms. For example, freedom of expression may be limited to protect people from hate speech. The second is if the federal government invokes the ‘notwithstanding’ clause, articulated in section 33 of the Charter (Centre for Constitutional Studies, n.d.). This has rarely been used and has a time limit of five years.

The Charter protects several labour relations-related rights under sections 2 (fundamental freedoms) and 15 (equality rights). Specifically, Canadians have the fundamental right to:

- organize and join a union

- collectively bargain with the employer

- strike against the employer

- picket or distribute information

- promote union beliefs and philosophy

Equality rights also protect workers by requiring non-discrimination in union membership, collective bargaining, and representation of members in processes such as grievances and arbitration.

Section 2 Fundamental Freedoms & Section 15 Equality Rights

“2. Everyone has the following fundamental freedoms:

- (a) freedom of conscience and religion;

- (b) freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication;

- (c) freedom of peaceful assembly, and;

- (d) freedom of association”

“15. Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

(Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, 1982, s 2, 15)

While today, unions and their members enjoy the protection of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, these rights were not present and obvious when the Constitution Act of 1982 was signed. Although members of the Canadian labour movement were asked to participate in Special Join Committee meetings to provide input and feedback on the document, they refrained from doing so. While there was decent interest among union leaders and members of provincial and federal labour federations, ultimately, the decision came down to a vote of the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) membership, who agreed to stay out of the constitutional debate. (Savage & Smith, 2017).

According to Savage & Smith (2017), this ‘constitutional paralysis’ boiled down to a few key concerns:

- Avoid alienating the Quebec Federation of Labour (QFL) — The province of Quebec and its premier, Rene Levesque, opposed the Charter and the patriated constitution. The Quebec Federation of Labour (QFL) held membership in the CLC and rallied around their premier and his opposition. The CLC realized that participating in Charter discussions could create a rift between the two organizations.

- A lack of agreement among the New Democratic Party (NDP) members on the constitution — Since this political party had been the main ally of the labour movement, there was a desire to avoid amplifying the internal divide.

- A general distrust of what the Charter meant for worker’s rights and protections — There was a possibility that the Charter could strengthen protections previously won and provided in existing legislation. However, there was also a general distrust of the courts and the possibility that the Charter could weaken the collective rights fundamental to the labour movement.

The different perspectives on the Constitution within the labour movement at the time are best summarized with quotes from the individuals who took part in these debates during and after the signing. Some felt strongly that the courts were not the place for labour rights:

At an April 1985 meeting of the Saskatchewan Government and General Employees Union (SGEU), Larry Brown, the union’s chief executive officer, summed up perfectly the union movement’s historical antipathy towards the courts when he warned members of his own union that the Charter would not be a panacea for public sector workers, pointing out that “working people have made their progress in the streets and on picket lines, in meetings and demonstrations, in struggle and confrontation…not in the halls of justice” (SGEU, 1985,3). Brown’s message was clear: labour could not rely on the courts to advance workers’ interests (Savage & Smith, 2017).

While others believed a healthy respect for the possibility of accruing more rights was in order:

Despite Brown’s misgivings, about the Charter, National Union of Public and General Employees (NUPGE) president John Fryer encouraged SGEU members to accept the Charter as a political reality that could not be ignored, arguing, “It is the duty of the trade union movement to do all we can to use the Charter and its provisions to protect and expand the existing rights of our membership” (SGEU 1985, 47). Fryer believed that the Canadian labour movement had to develop a strategic plan to deal with the Charter in order to ensure that it did indeed “protect and expand” the right of workers (Savage & Smith, 2017).

What transpired in the years following 1982 was precisely what Larry Brown opposed. The labour movement brought a series of constitutional challenges and court battles to the Supreme Court of Canada to ensure that the rights of unionized workers were, in fact, fundamental freedoms.

Early Charter Challenges

Some of the labour movement’s fears about the Charter were rooted in the new constitution’s emphasis on individual rights versus collective rights. While others believed that there was hope to strengthen worker protections through section 2(d) (freedom of association) and section 15 (equality rights) (Savage & Smith, 2017). The only way to tell was for unions or labour organizations to test the Charter was to bring complaints forward through the course.

The 1970s and 1980s were economically tough in Canada. The country was experiencing high inflation, and in an attempt to curtail this, the federal government passed wage control legislation. As a result, public sector unionized workers saw their ability to freely collectively bargain and strike also restricted.

In 1982, multiple unions challenged the Ontario government’s inflation legislation, which allowed them to extend the life of collective agreements and ultimately eliminate the right to strike (Savage & Smith, 2017). Although the Supreme Court offered recognition that section 2(d) did protect the right to collectively bargain and strike, they ultimately found that the Ontario government’s legislation was ‘within reasonable limits’ and, thus, still constitutional.

A further case between the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (RWDSU) and the Saskatchewan government in 1985 saw a 2–1 recognition of the right to strike in the dairy industry. However, despite this Charter win, the provincial government invoked the notwithstanding clause to keep the workers from going on strike (Savage & Smith, 2017).

While some of these first challenges saw at least a partial recognition that collective labour rights were protected in the Charter, the courts and governments continued to find ways to limit unions and unionized workers’ ability to take action.

One of the most significant early Charter challenges was the 1986 case of the Retail, Wholesale, and Department Store Union (RWDSU) vs. Dolphin Delivery. At the heart of this case was whether the fundamental freedoms in section 2(b) of the Charter applied to common law, the courts, and private actions. The RWDSU was locked out by their employer, Purolator Courier, and were secondary picketing at Dolphin Delivery, a company that delivered packages for Purolator during the labour dispute. Dolphin Delivery obtained an injunction against RWDSU from the British Columbia courts to stop the secondary picket.

The workplace fell under federal jurisdiction, but the Canada Labour Code (1985) was silent on secondary picketing. As a result, the case fell under common law to decide if the injunction was lawful. Thus, it was up to the Supreme Court to decide if court orders under common law and disputes between private parties fell under the provisions of the Charter.

In the end, the Supreme Court justices did not find that the Charter applied to the courts nor that an injunction was a form of government action because the courts were involved. They further applied section 32 of the Charter narrowly. This section states that the Charter only applies to actions of the Parliament, the Government of Canada, and the provinces, not private actions. As a result, the appeal was dismissed, and the injunction against the secondary picket was upheld.

The Labour Trilogy

In 1987, three additional cases were brought before the Supreme Court of Canada (SCC) to try and establish that the right to collective bargaining and strike was constitutional under section 2(d) (freedom of association). The three cases were:

- Reference re Public Service Employee Relations Act (Alta), [1987] 1 SCR 313 (later referred to as the Alberta Reference)

- PSAC v. Canada, [1987] 1 SCR 424

- RWDSU v. Saskatchewan, [1987] 1 SCR 460

In their decision, the SCC Justices took a narrow view of section 2(d). They concluded that Charter rights accrued to individuals and that collective bargaining and striking against an employer were inherently collective rights. Members of the labour movement argued that the very nature of associating was collective, and thus, the two were intertwined. The Alberta Union of Public Employees responded to the decision in Reference re Public Sector Employee Relations Act (Alta), with this statement:

Combing the definition of “freedom” with that of “association” leads to this: Persons are not to be restrained from engaging in common purposes or actions. At a minimum, anything which may be done by one person may be done by a combination of persons. The purpose of the guarantee of “freedom of association” is to provide a constitutional protection allowing persons to do together what they are permitted to do alone. Any act that may be lawfully done by one person may not be prohibited merely because it is to be done by a group of persons – unless the prohibition of the group activity can be justified by s.1. (Savage & Smith, 2017 p. 86).

While the majority of the justices agreed that limits on collective rights were appropriate and, thus, these cases were unsuccessful in their mission, it was not unanimous. In their dissent to the Alberta Reference, Chief Justice Dickinson and Chief Justice Wilson asserted that the right to collectively bargain and strike was protected by section 2(d):

In the context of labour relations, the guarantee of freedom of association in s. 2(d) of the Charter includes not only the freedom to form and join associations but also the freedom to bargain collectively and to strike. The role of association has always been vital as a means of protecting the essential needs and interests of working people. Throughout history, workers have associated to overcome their vulnerability as individuals to the strength of their employers, and the capacity to bargain collectively has long been recognized as one of the integral and primary functions of associations of working people. It remains vital to the capacity of individual employees to participate in ensuring equitable and humane working conditions. Under our existing system of industrial relations, the effective constitutional protection of the associational interests of employees in the collective bargaining process also requires concomitant protection of their freedom to withdraw collectively their services, subject to s. 1 of the Charter. Indeed, the right of workers to strike is an essential element in the principle of collective bargaining (Reference Re Public Service Employee Relations Act (Alta.), 1987).

While these constitutional limitations remained for many years, unions and members of the Canadian labour movement, especially those representing public sector unions, were not giving up on the fight to make collective bargaining rights and the right to strike fundamental freedoms for all Canadians.

The New Labour Trilogy

Between 1987 and 2000, little changed on the labour matter at the SCC and in the Justices’ minds. They continued to apply a narrow perspective to section 2(d), maintaining that the right to belong to an association did not necessarily mean it had to be an association recognized by the statute. This became clear when members of the RCMP challenged legislation that prohibited them from unionizing, and the SCC disagreed that the legislation violated their freedom to associate (Hurst, 2017).

However, the 2001 Dunmore v Canada (AG) case caused the tide to shift when there was a unanimous decision that excluding agricultural workers from the Ontario labour legislation violated section 2(d) of the Charter (Hurst, 2017). The Ontario government was still able to pass legislation that did not allow agricultural workers to engage in collective bargaining. However, the case was still an important development that was expected to spark additional challenges (McQuarrie, 2014).

One such challenge came from the Health Services and Support – Facilities Subsector Bargaining Assn. v. British Columbia case in 2007 when a group of healthcare unions took the British Columbia government to the SCC after the government passed Bill 29. This controversial bill allowed the government to unilaterally change collective agreements by removing language that protected healthcare workers’ jobs and prevented subcontracting. In this case, the SCC decided this violated the right to collective bargaining as part of section 2(d) (freedom of association) (McQuarrie, 2014).

In 2015, three additional cases came before the SCC, culminating in the most current and impactful trilogy of Charter cases.

- Meredith v. Canada (Attorney General), [2015] 1 SCR 125

- Mounted Police Association of Ontario v. Canada (Attorney General), [2015] 1 SCR 3

- Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v. Saskatchewan, [2015] 1 SCR 245

In the first case, Meredith v. Canada (Attorney General) (2015), the Supreme Court had to consider wage restraint legislation implemented by the RCMP following the 2008 economic crisis. Through the non-unionized Staff Relations Representatives Process (SRRP), RCMP members and the employer agreed upon wage increases between 2008 and 2010. The RCMP implemented the Expenditure Restraint Act (ERA) (2009) to address the changing economic times and rolled back the increases (Barrett & Poskanzer, 2015).

On the same day, January 16, 2015, the SCC found that excluding the RCMP members from the Public Sector Staff Relations Act (PSSRA) (1985) was unconstitutional under section 2(d). This overturned their earlier decision on the matter. In this case, the justices found that the existing SRRP model did not allow members to have independent management, nor did it allow for meaningful collective bargaining as they could only have input into their contract.

This was a departure from the more narrow definitions applied to previous section 2(d) challenges by labour movement members. It seemed that the SCC now preferred to interpret freedom of association so it included collective rights, specifically collective bargaining.

The Court held that there are two essential features of a meaningful process for collective bargaining – (1) employee choice and (2) independence from employers of a degree “sufficient to enable [employees] to determine their collective interests and meaningfully pursue them.” (Broad & Hines, 2015)

The Saskatchewan decision is the most significant case of this new labour trilogy. In 2008, the Saskatchewan government implemented new legislation called The Public Service Essential Services Act (2008). This new legislation allowed the province to prohibit employees working in the public service from striking if they are deemed an essential service. The act also allowed the government to unilaterally designate any public service position as essential.

On behalf of a number of unions and labour organizations, the Saskatchewan Federation of Labour filed a complaint with the SCC, claiming this legislation violated section 2(d) of the Charter (Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v. Saskatchewan, 2015). While there was some dissent, most justices agreed that this action impacted the employee’s freedom of association due to the close link between meaningful and effective collective bargaining (already a Charter right) and the right to strike. Writing for the majority, Justice Abella had this to say:

The right to strike is an essential part of a meaningful collective bargaining process in our system of labour relations. The right to strike is not merely derivative of collective bargaining, it is an indispensable componentof that right. Where good faith negotiations break down, the ability to engage in the collective withdrawal of services is a necessary component of the process through which workers can continue to participate meaningfully in the pursuit of their collective workplace goals. This crucial role in collective bargaining is why the right to strike is constitutionally protected by s. 2(d) (Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v. Saskatchewan, 2015).

As one might imagine, the labour movement celebrated these victories and newly established protections. However, many critics also expressed concerns about the uncertainty these changes might bring due to the justices breaking precedence (Hurst, 2017) and the foray into collective actions instead of individual association. What is certain is that despite not having input in crafting the Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1982), the labour movement has been active in shaping the interpretation of this vital piece of legislation.

Fundamental Freedoms & Union Activity

The fundamental freedoms listed below under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms currently protect the following union activities.

- (b) freedom of thought, belief, opinion and expression, including freedom of the press and other media of communication — right to promote union belief and philosophy.

- (c) freedom of peaceful assembly — right to picket.

- (d) freedom of association — right to belong to a union, collectively bargaining, and strike against the employer.

(Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, 1982, s 2)

Labour Legislation

Labour laws apply to both federal and provincial employers and workers. Federally regulated workplaces must follow the Canada Labour Code (1985), and provincially regulated workplaces follow the labour relations code or act in their province. While there are some differences between the provincial laws and the Canada Labour Code, there are also many similarities.

For example, some provinces have provisions for specific industries, such as construction, higher education, and public sector employees. Many include language about essential service designations, and in some provinces, labour laws include occupational health and safety provisions. In other provinces, these provisions are contained in other acts and regulations. For example, British Columbia, has separate laws for public sector labour relations and occupational health and safety. This is why understanding your workplace’s legal jurisdiction is so important.

Differences aside, many provisions are found in all of the labour relations laws in Canada. Some common clauses address the following:

- procedures for unions and workers to form a bargaining unit and for the union to become the exclusive bargaining agent for a group of employees in a workplace

- definitions of and processes to address unfair labour practices by the employer or the union

- processes for dispute resolution, referred to as grievance processes

- requirements for minimum durations of collective agreements

- procedures, timelines, and pre-conditions for legal strikes and lockouts

- requirements to establish a labour relations board to provide oversight, administration, and enforcement of the legislation

Labour Relations Boards

Labour relations boards are quasi-judicial bodies, meaning they operate similarly to courts but less formally (Fulcrum Law Corporation, n.d.). Boards can make decisions on matters related to labour legislation and apply remedies and penalties as needed. Labour boards can also provide support for conflict resolution through mediation, arbitration, and conciliation services as required or by request from unions or employers. The federal and provincial governments fund the labour relations boards in each jurisdiction, and board members are appointed by the government. Generally, boards are made up of an equal number of union and employer representatives.

Alberta Labour Relations Board’s Responsibilities

“The Alberta Labour Relations Board is the independent and impartial tribunal responsible for the day-to-day application and interpretation of Alberta’s labour laws. It processes applications and holds hearings. The Board actively encourages dispute resolution, employs officers for investigations and makes major policy decisions. There are Board offices in both Edmonton and Calgary.

The Labour Relations Code encourages parties to settle their disputes through honest and open communication. The Board offers informal settlement options to the parties, but it also has inquiry and hearing powers to make binding rulings whenever necessary.”

(Alberta Labour Relations Board, n.d.)

As you explore various topics and processes in labour relations, the role of labour relations boards will become clearer. For now, it is sufficient to understand that the board must uphold and administer labour laws in its jurisdiction, and its specific powers are articulated in that code or act. You are encouraged to review the legislation that applies in your province or territory by visiting their website using the links in Table 2.1 below. The exercise that follows this table will help guide your exploration.

| Province | Name of Labour Relations Law |

|---|---|

| British Columbia | Labour Relations Code (1996) |

| Alberta | Labour Relations Code (2000) |

| Saskatchewan | Saskatchewan Employment Act (2013) |

| Manitoba | Labour Relations Act (1987) |

| Ontario | Labour Relations Act (1995) |

| Quebec | Labour Code/Code du Travail (1996) |

| New Brunswick | Industrial Relations Act (1973) |

| Nova Scotia | Trade Union Act (1989) |

| Prince Edward Island | Labour Act (1996) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Labour Relations Act (1990) |

Apply Your Learning

Visit the website for your provincial labour law or the Canada Labour Code if your workplace falls under federal jurisdiction. Review the table of contents of the act or code or visit their website home page and see if you can answer the following questions. Answers will vary depending on your jurisdiction, so an answer key is not provided for this exercise.

- What percentage of employees in a workplace need to show their support for union representation to apply for certification to the labour board? (HINT: looks for a section on ‘acquiring bargaining rights’)

- When can a union or employer initiate collective bargaining?

- When are strikes or lockouts prohibited?

- Under what circumstances can the employer or union request mediation services from the labour board?

Human Rights Legislation

As you learned from reading about the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, equality and equal treatment under the law free of discrimination are fundamental rights in Canada. However, in addition to these fundamental rights, human rights legislation provides specific protections against discrimination in employment. Both the federal and provincial governments have human rights laws and regulatory bodies to help enforce these laws. This is in keeping with the jurisdictional model described above.

Human rights laws are crucial to employers and workers as they articulate protected grounds (sometimes called prohibited grounds or personal characteristics) for discrimination in employment. For example, in all jurisdictions, it is illegal to refuse to employ someone because of their sex or sexual preference.

Employment discrimination can be direct or intentional, like the previous example, but can also be systemic or unintentional. The latter is often harder to identify and can include scenarios where an organization’s policies or practices discriminate but are not intended to. The most referenced example of this is the case of Tawny Meiorin.

British Columbia (Public Service Employee Relations Commission) v. BCGSEU (1999)

Tawny Meiorin was a female forest firefighter. She had successfully performed the job for three years, but upon her return for a new season, she was subjected to a new aerobic fitness test. Meiorin was unable to meet the standard and was terminated. Meiorin and her union, the BC General and Service Employees Union filed a human rights complaint saying the standard discriminated against women because it was based on a requirement that did not account for differences in the performance of men and women.

The case went to the Supreme Court of Canada, favouring Meiorin and her union. In particular, the high court found that the test was not reasonably necessary for safe and effective job performance. The result of this led the SCC to devise a three-part test for employers to establish Bona Fide Occupational Requirements (BFOR). This included the following:

- Rational connection — The standard served a purpose rationally connected to the performance of the job.

- Good faith — The standard was adopted in an honest and good faith belief that it was necessary to fulfil legitimate, work-related purposes.

- Reasonably necessary — The standard was reasonably necessary to the accomplishment of that legitimate, work-related purpose (i.e. employers would need to show it would be impossible to accommodate the claimant without imposing undue hardship on the employer).

(Women’s Legal Education & Action Fund, n.d.)

Human rights laws are important to be aware of in unionized environments beyond employment decisions. Unions and employers must ensure that their collective bargaining agreements do not violate human rights laws, which may require periodic updates as legislation changes. Unions must also be mindful that they do not intentionally or unintentionally discriminate within their own practices. For example, during their elections for local leadership positions or through any other administrative or organizational processes.

To better understand the various protected grounds and complaint processes, visit the webpage for your jurisdiction’s human rights regulatory body using Table 2.2. Then, familiarize yourself with the act by answering the questions that follow.

| Jurisdiction | Name of Human Rights Legislation |

|---|---|

| Federal | Canada Human Rights Act (1985) |

| British Columbia | British Columbia Human Rights Code (1996) |

| Alberta | Alberta Human Rights Act (2000) |

| Saskatchewan | Saskatchewan Human Rights Code (2018) |

| Manitoba | Manitoba Human Rights Code (1987) |

| Ontario | Ontario Human Rights Code (1990) |

| Quebec | Quebec Charter of Human Rights (1975) |

| New Brunswick | New Brunswick Human Rights Act (2011) |

| Nova Scotia | Nova Scotia Human Rights Act (1989) |

| Prince Edward Island | PEI Human Rights Act (1975) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Newfoundland and Labrador Human Rights Act (2010) |

Apply Your Learning

Find the human rights legislation that applies to your jurisdiction. Then, find your collective agreement (if you are in a union) or your employer’s non-discrimination policy (if they have one). Answer the following questions.

- How many protected grounds are listed in the human rights law? Do any of these surprise you?

- Review your collective agreement or non-discrimination policy. Do you see similar language reflected in both documents? Any discrepancies?

- What is the process for filing complaints under the human rights law in your jurisdiction?

Employment Standards Legislation

Consistent with previous types of legislation, employment standards exist for all jurisdictions. These standards apply to unionized and non-unionized workers in a particular jurisdiction and provide minimum requirements for employers. This might include provisions for minimum wages, work hours, overtime, and employee leaves.

As minimum requirements, employment standards cannot be ignored or over-written in collective agreements. For example, suppose the minimum wage in your jurisdiction is $18.35 per hour. In that case, a union and employer cannot negotiate a collective agreement that offers an employee $16.50 per hour as the agreement would violate an employment standard. However, collective agreements can (and often do) provide wages and protections exceeding minimum standards.

Employment standard regulations are also codified in acts or codes similar to labour laws. In British Columbia, the Employment Standards Act (1996) is the legislation administered by the Employment Standards Branch, which falls under the responsibility of the Ministry of Labour. Enforcement of employment standards is generally based on complaints, but the director may also initiate investigations. Unionized workers are usually unable to make complaints through employment standards as they have a grievance process available to them through their collective agreement.

Public Sector Labour Relations Legislation

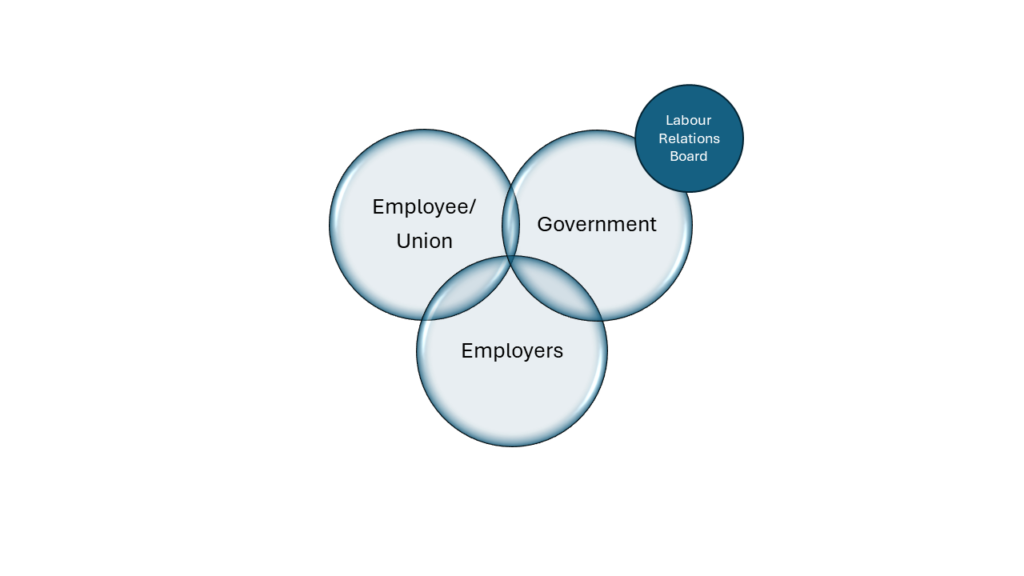

One unique feature of the labour relations legal framework is the relationship between some unions and the government. The labour relations system, which you will learn more about in the theories model, includes many potential actors. However, there are three main actors involved in this system:

- employers

- unions representing employees

- the government

The labour relations board acts on behalf of the government to regulate the activities of these actors to ensure they are compliant with labour legislation (see Figure 2.3).

But what happens when the government is also the employer? As you learned from the section on the Charter of Rights and Freedoms and Chapter 1, many unionized workers are employed in the public sector. When this happens, the provincial or federal government becomes an employer. However, government representatives also make the laws, including labour and employment laws. As you can imagine, this creates an even greater power imbalance between the employer and employees. Public sector labour relations legislation is created in most jurisdictions to mitigate this imbalance.

Figure 2.1 near the beginning of the chapter outlines many types of workplaces that belong to the federal public service, but each province also has its own public service. A provincial public sector labour relations act would protect employees who work within provincial government departments, such as the Employment Standards branch and the Provincial Treasury department.

However, several organizations are considered part of the public sector but are not government departments. For example, universities, courts, school districts, and health authorities receive funding from the government to operate and are accountable to various provincial government departments and processes. These types of organizations are often called para-public sector organizations because employees are not directly hired by the provincial government, but their employment is affected by government oversight.

Provinces may have separate labour legislation specific to these para-public sector organizations to address this unique relationship and help maintain fairness in labour relations matters. For example, the province of Newfoundland and Labrador has public sector labour legislation for people working in the fishing industry, education, and occupational health and safety roles (Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Relations Board, 2023).

The number of acts or codes that govern public sector roles in your jurisdiction may vary. One way to uncover what applies in your jurisdiction is to visit the Ministry of Labour or Employment website for your province or territory. Federal public sector labour legislation can be found on the Justice Laws Website on the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act (2003) page.

Conclusion

Labour relations legislation is a complex framework designed to balance the differing interests of employees, unions, and employers. Provincial and federal governments create labour laws to address and regulate labour relations activities, such as union certification, collective bargaining, and dispute resolution, which are enforced and administered by labour relations boards.

However, unionized workers and workplaces must also adhere to other legislation and statutes that apply to their jurisdiction. This includes the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, human rights legislation, employment standards legislation, occupational health and safety regulations, and, in some cases, industry-specific legislation.

This chapter provides a broad overview, but future chapters will include specific legislation that applies to that topic. As you may be starting to see, understanding labour relations requires you to understand the laws surrounding and interacting with it. This understanding is crucial for anyone involved in labour relations, whether you are an HR professional, a union representative, or a member of management.

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.1 “Distribution of Employees in the Federal Public Sector and the Federally Regulated Private Sector” by Employment and Social Development Canada (2022b), via Government of Canada, is used under the Government of Canada Terms and Conditions.

- Figure 2.2 “Signing of the Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982” by Robert Cooper and Library Archives Canada (1982), via Government of Canada, is used under the Government of Canada Terms and Conditions.

- Figure 2.3 “Actors in the labour relations system” was created by the author under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Alberta Human Rights Act, R.S.A. c. A-25.5 (2000). https://albertahumanrights.ab.ca/media/1utjxb3e/alberta-human-rights-act.pdf

Alberta Labour Relations Board. (n.d.). About the Board. Retrieved June 12, 2024, from http://www.alrb.gov.ab.ca/aboutboard.html

Barrett, S., & Poskanzer, E. (2015, January 17). Freedom of association includes right to independent bargaining agent. Goldblatt Partners. https://goldblattpartners.com/experience/notable-cases/post/freedom-of-association-includes-right-to-independent-bargaining-agent/

British Columbia (Public Service Employee Relations Commission) v. BCGSEU, [1999] 3 SCR 3. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/1724/index.do

Broad, P. E., & Hines, M. A. (2015, February 5). Supreme court expands “freedom of association” and recognizes right to strike. Hicks Morley. https://hicksmorley.com/2015/02/05/supreme-court-expands-freedom-of-association-and-recognizes-right-to-strike/

Canada Labour Code, R.S.C. c. L-2 (1985). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/ACTS/L-2/index.html?wbdisable=false

Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 7, Part 1 of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), c 11.

Canadian Human Rights Act, R.S.C. c. H-6 (1985). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/h-6/

Centre for Constitutional Studies. (n.d.). Charter. https://www.constitutionalstudies.ca/the-constitution/charter/

Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, C.Q.L.R. c. C-12 (1975). https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/document/cs/C-12

Cooper, R. & Library and Archives Canada. (1982). Signing of the Proclamation of the Constitution Act, 1982 [Image]. Government of Canada. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=3206003&lang=eng

Dunmore v. Ontario (Attorney General), [2001] 3 SCR 1016. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/1936/index.do

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2022a, February 24). A portrait of the federally regulated private sector. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/portfolio/labour/programs/labour-standards/reports/issue-paper-portrait-federally-regulated-private-sector.html

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2022b, February 23). Distribution of employees in the federal public sector and the federally regulated private sector [Image]. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/employment-social-development/corporate/reports/labour-transition-binders/minister-labour-2021/employee-distribution-infographic.html

Employment Standards Act, R.S.B.C. c. 113 (1996). https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96113_01

Expenditure Restraint Act, S.C. c. 2, s. 393 (2009). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/E-15.5/page-1.html

Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act, S.C. c. 22 (2003). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/P-33.3/

Fitz-Morris, J. (2015, January 16). RCMP officers have right to collective bargaining, Supreme Court rules. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/rcmp-officers-have-right-to-collective-bargaining-supreme-court-rules-1.2912340

Fulcrum Law Corporation. (n.d.). What is quasi-judicial. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://www.fulcrumlaw.ca/law-dictionary/quasi-judicial

Health Services and Support – Facilities Subsector Bargaining Assn. v. British Columbia, [2007] 2 SCR 391. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/2366/index.do

Hogg, P. W. (1987). The dolphin delivery case: The application of the charter to private action. Saskatchewan Law Review, 51(2), 273–280. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works/781/

Human Rights Act, R.S.N.B. c. 171 (2011). https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/nbhrc/human-rights-act/acts-and-regulations.html

Human Rights Act, R.S.N.S. c. 214 (1989). https://nslegislature.ca/sites/default/files/legc/statutes/human%20rights.pdf

Human Rights Act, R.S.P.E.I. c. H-12 (1975). https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/legislation/H-12%20-Human%20Rights%20Act.pdf

Human Rights Act, S.N.L. c. H-13.1 (2010). https://www.assembly.nl.ca/legislation/sr/statutes/h13-1.htm

The Human Rights Code, C.C.S.M. c. H175 (1987). https://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/statutes/ccsm/_pdf.php?cap=h175

Human Rights Code, R.S.B.C. c. 210 (1996). https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/00_96210_01

Human Rights Code, R.S.O. c. H.19 (1990). https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90h19

Hurst, L. G. (2017). A new hope, or a charter menace? The new labour trilogy’s implications for labour law in Canada. Appeal: Review of Current Law and Law Reform, 22, 25–44. https://journals.uvic.ca/index.php/appeal/article/view/16749

Industrial Relations Act, R.S.N.B. c. I-4 (1973). https://laws.gnb.ca/en/tdm/cs/I-4

Labour Act, R.S.P.E.I. c. L-1 (1988). https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/legislation/l-01-labour_act.pdf

Labour Code, C.Q.L.R. c. C-27 (1996). https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/document/cs/C-27/20021002

Labour Relations Act, R.S.M. c. L10 (1987). https://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/statutes/ccsm/l010.php?lang=en

Labour Relations Act, R.S.N.L. C. L-1 (1990). https://www.assembly.nl.ca/legislation/sr/statutes/l01.htm

Labour Relations Act, S.O. c. 1 Sched. A (1995). https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/95l01

Labour Relations Code, R.S.A. c. L-1 (2000). https://kings-printer.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/L01.pdf

Labour Relations Code, R.S.B.C. c. 244 (1996). https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96244_01

McIntosh, A., & Azzi, S. (2012, February 6). Constitution Act, 1982. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/constitution-act-1982

McQuarrie, F. (2015). Industrial relations in Canada (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Melnitzer, J. (2016, February 16). The right to strike: Supreme Court’s labour trilogy has wide ranging impacts. Lexpert. https://www.lexpert.ca/archive/the-right-to-strike-supreme-courts-labour-trilogy-has-wide-ranging-impacts/350313

Meredith v. Canada (Attorney General), [2015] 1 SCR 125. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/14576/index.do

Mounted Police Association of Ontario v. Canada (Attorney General), [2015] 1 SCR 3. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/14577/index.do

Neuman, C. (2016). The Supreme Court’s new labour trilogy: Momentous decisions and modest critique. Constitutional Forum / Forum Constitutionnel, 25(2), 17–26. https://doi-org.ezproxy.tru.ca/10.21991/c9b685

Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Relations Board. (2023). Legislation. Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. https://www.gov.nl.ca/lrb/board/legislation.html

PSAC v. Canada, [1987] 1 SCR 424. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/206/index.do

Public Service Essential Services Act, S.S. c. P-42.2 (2008). https://www.canlii.org/en/sk/laws/stat/ss-2008-c-p-42.2/latest/ss-2008-c-p-42.2.html

Public Service Staff Relations Act, R.S.C. c. P-35 (1985). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/p-35/

Reference Re Public Service Employee Relations Act (Alta.), [1987] 1 SCR 313. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/205/index.do

RWDSU v. Dolphin Delivery Ltd., [1986] 2 SCR 573. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/181/index.do

RWDSU v. Saskatchewan, [1987] 1 SCR 460. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/207/index.do

Saskatchewan Employment Act, S.S. c. S-15.1 (2013). https://pubsaskdev.blob.core.windows.net/pubsask-prod/78194/S15-1.pdf

Saskatchewan Federation of Labour v. Saskatchewan, [2015] 1 SCR 245. https://decisions.scc-csc.ca/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/14610/index.do

The Saskatchewan Human Rights Code, S.S. c. S-24.2 (2018). https://saskatchewanhumanrights.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Code2018.pdf

Savage, L., & Smith, C. W. (2017). Unions in court: Organized labour and the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. UBC Press.

Statistics Canada. (2024). Employment by industry, annual (Table No. 14-10-0202-01) [Table]. Government of Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1410020201

Trade Union Act, R.S.N.S. c. 475 (1989). https://nslegislature.ca/sites/default/files/legc/statutes/trade%20union.pdf

Women’s Legal Education & Action Fund. (n.d.). British Columbia (Public Service Employee Relations Commission) v. BCGSEU (1999). https://www.leaf.ca/case_summary/british-columbia-v-bcgseu-1999/

Apply Your Learning Answers

- provincial

- federal

- federal

- provincial

Long Descriptions

- Federal public sector (FPS)

- Group 1 — Core public administration (CPA) (including RCMP) — 267,700

- Group 2 — Separate agencies — 73,900

- Group 3

- Canadian Armed Forces Regular Force — 65,200

- Reservists — 37,500

- Group 4 — Crown corporations and other (other includes MINO exempt staff (714), employees of the House of Commons, Senate, the Library of Parliament, and others) — 131,700

- Total — 575,900

- Federally regulated private sector (FRPS)

- Group 5

- Transportation (road, air, rail, and maritime) — 310,400

- Banks — 260,400

- Telecom and broadcasting — 138,400

- Postal and pipelines — 58,200

- Feed, flour, seed, and grain — 18,000

- Miscellaneous (e.g., Uranium mining, oil & gas exploration in the territories) — 7,800

- Indigenous government on First Nations reserves — 35,000

- Total — 828,200

- Group 5

- Total for FPS and FRPS — 1.40 million

Quasi-judicial refers to a legal process or decision-making authority that is vested in an administrative body or tribunal, which has the power to make decisions that are similar to those made by a court of law. (What Is Quasi-Judicial | BC Business Legal Library, n.d.)

Personal characteristic (e.g., gender or ethnic background) defined in provincial and federal human rights legsilation as factors that are forbidden from being used as the basis of discrimination (McQuarrie, 2014).