4 Labour History: A Growing Movement

Melanie Reed

Learning Objectives

- Recall key events in Canadian labour relations history.

- Describe the evolution of modern-day labour laws in Canada.

- Explain the impact of critical historical events on modern-day labour relations.

Introduction

By the late 1800s, it was evident that Canada was in the throws of an industrial revolution. With economic activity expansion came highs and lows in production and employment. This volatility gave the blooming labour movement a new sense of vigour that manifested through increased organizing and labour action against employers. Craft unions increased their efforts in their existing locations and began expanding into new cities, where industrialization efforts also expanded. Workers who were ignored by the craft unions did not sit on the sidelines but rather demonstrated their discontent with capitalist employers through strikes and militancy regardless of representation by a union. There was also a growing effort to organize labour movement members by developing labour councils and a national labour congress. This chapter will highlight some key moments that punctuated the next century of Canadian labour.

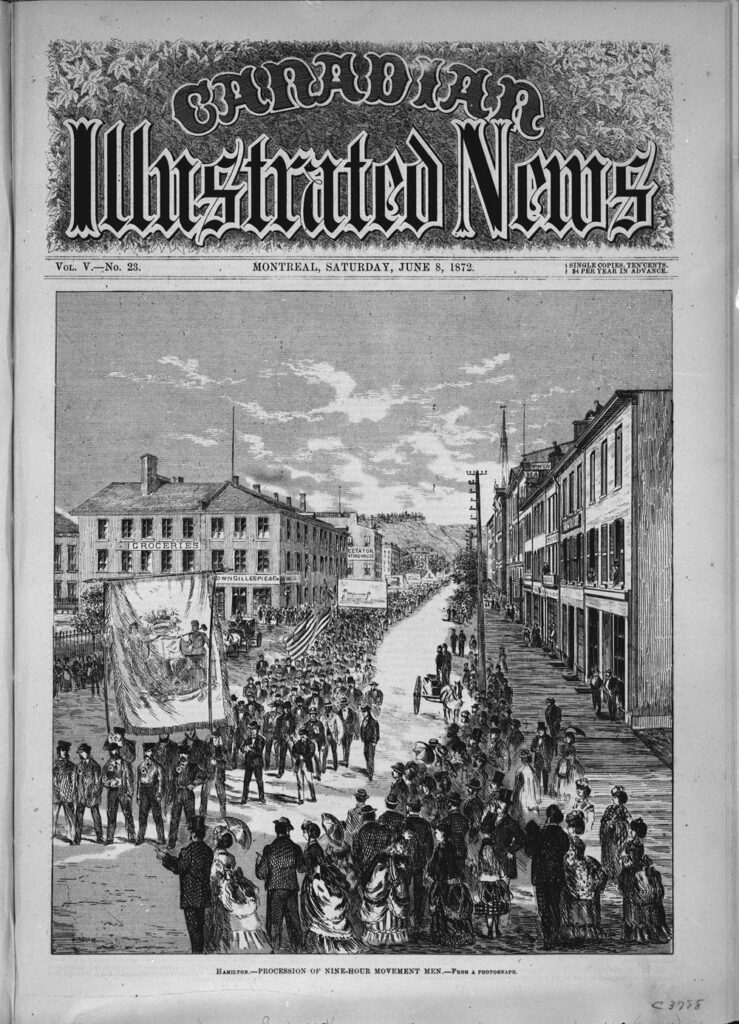

The Nine-Hour Movement & Trade Union Act, 1872

The late 1800s marked a period of burgeoning resistance against the difficult conditions faced by wage labourers in Canada. Among the significant events that catalyzed change was the Nine-Hour Movement of 1872, a pivotal worker-led campaign inspired by similar efforts in Britain. This movement aimed to convince employers to limit the workday to nine hours, significantly improving the quality of life for workers.

Beginning in January 1872, the movement gained momentum through a series of organized meetings and strikes across Montreal, Hamilton, and various Ontario cities. It drew support from diverse groups, including blacksmiths, carpenters, typographical workers, and unionized and non-unionized labourers. The collective effort highlighted the widespread desire for reform across different trades and industries.

Employers’ reactions to the Nine-Hour Movement varied widely. Some were sympathetic and conceded to the workers’ demands, offering shorter workdays. However, most employers collectively resisted, fearing such changes would harm their businesses. Despite the pushback, the movement’s persistence signalled a growing discontent that could not be easily ignored.

While the movement did not immediately achieve its goal of a nine-hour workday, it was far from a failure. The turning point came in April 1872 when Toronto printers went on strike (Palmer, 2006). In response, Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald introduced the Trade Union Act, marking Canada’s first official piece of labour legislation. This act legalized union membership, which had previously been considered a conspiracy or crime, laying the groundwork for future protections of workers’ rights. Although subsequent legislation made picketing illegal, and there were limits on the act’s protection for unions, the foundation had been set for more comprehensive labour laws (Heron & Smith, 2020).

The Nine-Hour Movement is often regarded as a catalyst for further labour activism and growing public and political awareness of workers’ rights. It also fostered unity among various unions, paving the way for establishing Canada’s first labour federation, the Canadian Labour Union, in 1873 (Heron & Smith, 2020; Palmer, 2006). This organization aimed to represent workers’ interests politically, even though it was not initially focused on organizing unions or negotiating with employers. Despite its limited geographical representation—primarily delegates from Ontario until 1878—the Canadian Labour Union’s formation underscored the importance of collective action in advocating for labour reforms. (Heron & Smith, 2020).

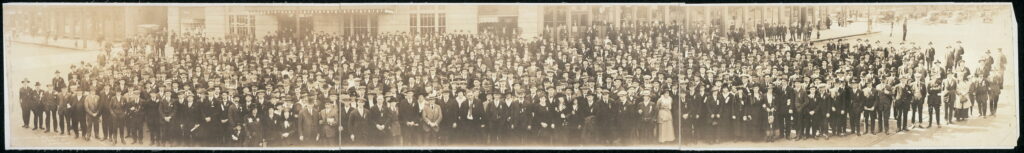

Trades and Labour Congress (TLC)

The Trades and Labour Congress (TLC) of Canada, which held its inaugural meeting in 1886, was a significant organization in the history of the Canadian labour movement. The TLC emerged as a coalition of Canadian affiliate unions of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) and members of influential labour groups like the Knights of Labor (Hebdon et al., 2020). This confluence of skilled and unskilled labour aimed to unify the diverse voices of Canadian workers and advocate for their rights collectively.

At its core, the TLC sought to address the socio-economic challenges workers faced and improve their living and working conditions. The Congress’s primary objective was articulated as follows: “to rally all the workers’ organizations to work to fashion new laws or amend existing laws, in the interests of those who must earn their living, while ensuring the well-being of the working classes (Kealey & Gagnon, 2006).” One of the TLC’s foremost strategies was to lobby the government for legislative changes that would benefit workers. Through persistent advocacy, they aimed to secure better wages, safer working conditions, and reduced working hours.

However, the path to a unified labour movement was fraught with challenges. By the early 1900s, ideological differences and strategic disagreements began to surface within the TLC. After the 1902 congress, these tensions culminated in the expulsion of 23 unions, including the Knights of Labor. This schism led to the formation of the National Trades and Labor Congress (NTLC), which eventually became the Canadian Congress of Labour (CCL) in 1927 (Hebdon et al., 2020).

For the majority of its existence, the TLC aligned practices with that of the AFL, which believed in exclusive jurisdiction (unions that represented a single trade), business or simple unionism (focused on improving conditions for their members) and political nonpartisanship (Hebdon et al., 2020). Over time, however, it prevented the TLC from representing issues unique to Canadian workers and unions. After 70 years of operation, the TLC merged with the CCL in 1956 and became the national federation for organized labour, the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) (Heron & Smith, 2020).

Industrial Disputes Investigation Act, 1907

The early 1800s and 1900s saw bursts of strike action in Canada due to increased immigration, industrial economic growth in resource-based sectors, and the development of two national railways (Cruikshank & Kealey, 1987). These disruptions led the Canadian government to pass legislation in 1900 called the Canadian Conciliation Act, which led to the creation of the federal Department of Labour. This act aimed to reduce the number of labour disputes and provide avenues for conciliators to encourage more amicable collective bargaining. The legislation also offered the opportunity for arbitration should conciliation not be successful, yet the services offered to employers and workers were purely voluntary. In 1903, after a series of railway strikes, the Railway Labour Disputes Act of 1903 was passed, resulting in the option for conciliation and arbitration by the request of either party to a railway labour dispute. This more specific piece of legislation was developed due to the importance of the railway to economic development and transportation (Williams, 1964).

While both The Canadian Conciliation Act and the Railway Labour Disputes Act were options for intervention in labour disputes, they formed a foundation for future legislation that compelled the parties to resolve their differences with government assistance. In March 1907, the Deputy Minister of Labour, William Lyon McKenzie, passed the Industrial Disputes Investigation Act (Marks, 1912). This new law was motivated by a series of strikes in the public utility and mining industries, which were critically important to Canada’s growing population and industrial complex. Unlike predecessors, this new legislation compelled employers and employees in the “transportation, resource and utility industries” to engage in conciliation before a strike or lockout occurred and serve a cooling-off period (Heron & Smith, 2020).

Although the impetus of this new legislation was to curtail strike activity in Canada’s flourishing industries and newly developing transportation network, industrial disputes increased after 1907. This was not the result of the legislation but rather of increases in union development, class differences, shifts in working conditions, industrial growth, wartime booms, and post-war depressions (Cruikshank & Kealey, 1987). The following table, adapted from Cruikshank & Kealey’s 1987 data collection efforts, illustrates the absolute number of strikes between 1890 and 1950, demonstrating increased activity after 1907.

Table 4.1 Canadian Strike Estimates by Decade, 1891-1950

| Number of Strikes | Number of Workers (000's) |

Duration in Person Days (000's) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1891-1900 | 511 | 78 | 1742 |

| 1901-1910 | 1548 | 230 | 5492 |

| 1911-1920 | 2349 | 521 | 10821 |

| 1921-1930 | 989 | 261 | 6626 |

| 1931-1940 | 1760 | 376 | 3444 |

| 1941-1950 | 2537 | 1133 | 14142 |

| Totals | 9694 | 2599 | 42267 |

Table 4.1 Adapted from Cruikshank, D., & Kealey, G. (1987). Strikes in Canada, 1891-1950: I Analysis. Labour/Le Travailleur, 20, 85–122.

Winnipeg General Strike

On May 15, 1919, approximately 30,000 unionized and non-unionized workers in Winnipeg, Manitoba, walked off the job in the largest general strike in Canada (Reilly, 2006). The Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council’s (WTLC) Strike Committee organized the strike. Through their efforts and the collective will of workers in public utilities, factories, retail stores, postal workers, emergency services and telephone and telegraph operators (Reilly, 2006), the City of Winnipeg was brought to a halt within hours.

The lead-up to the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 was a tumultuous period marked by profound economic, social, and political changes. World War I, which lasted from 1914 to 1918, drew many Canadians from various industries into military service, resulting in significant labour shortages. This scarcity of workers led to increased unionization, negotiations and improvements in wages, alongside the employment of women in roles traditionally held by men. However, the war also brought about deskilling in many trades and a tightening grip of management control over workers, increasing their discontent. Concurrently, inflation soared, eroding any wage gains and leaving many workers struggling to make ends meet.

The war years saw heightened government control and efforts by employers to suppress strikes, aiming to maintain production and order. The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution in Russia further fueled militant ideologies among Canadian workers, inspired by the prospect of radical change (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2024). As the war concluded in 1918, returning soldiers faced a bleak landscape of high unemployment, rampant inflation, and deplorable working and living conditions. There was a growing awareness of stark class disparities, and industrialists, deeply anti-union, feared a revolutionary wave similar to Russia’s. This fear was only heightened by the number of Eastern European immigrants Canada had attracted in the preceding decades. This volatile mix of economic hardship, social unrest, and political radicalism created a perfect scenario for one of Canada’s most significant labour actions, the Winnipeg General Strike.

Source: William McKeown. (2017, September 14). Winnipeg General Strike [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/pVKo6xEgjaI?si=S0BmauHsqnerkWYS

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to the video: Winnipeg General Strike

As the video illustrates, the strike began as an act of solidarity with the Building and Metal Trades workers who were denied the right to collectively bargain (Heron & Smith, 2020). The telephone operators, the “Hello Girls,” were the first to take action. Within 24 hours, overwhelming support for the strike from workers across various industries and unions was activated. However, these acts of solidarity in the streets of Winnipeg were met with powerful opposition from business owners and politicians through the Citizens Committee of 1000 (Reilly, 2006).

However, opposition to the strike did not stop there. All three levels of government, municipal, provincial and federal, also worked together and used their legislative power to ultimately cripple the strike. With the city police on the strikers’ side, the Northwest Mounted Police and special constables were brought in to patrol the parades and protests. On June 9th, the City of Winnipeg fired all the Winnipeg city police (Ross & Savage, 2023). By June 16th, the federal government amended the Immigration Act to allow the deportation of many strike leaders. It then altered the Criminal Code to expand the definition of conspiracy, allowing the arrests of the strike leaders based on suspicion, not evidence. (McQuarrie, 2014). Finally, on June 17th, these arrests happened when ten strike leaders were sent to jail.

A silent parade opposing the arrests was held on June 21st. Once again, the government acted swiftly when protesters started to vandalize a streetcar. The Northwest Mounted Police charged the streets and fired into the crowd, killing two strikers and wounding many others. The day became known as Bloody Saturday. Fearing further violence, the strike was called off a few days later, ending with over 3000 workers without a job (Ross & Savage, 2023).

Although it did not achieve immediate gains for workers, the Winnipeg General Strike played a crucial role in shaping the future of the labour movement in Canada. The strike united workers from various industries and backgrounds, demonstrating the power of collective action and setting the stage for a more organized and resilient labour force across the country. Despite the swift and harsh response from government and business leaders, the strike brought to light the deep social and economic inequalities faced by workers – something many workers still face today. It also highlighted the determination of the working class to fight for their rights, even in the face of significant opposition.

In the years following the strike, several of its leaders transitioned into political roles, using their experiences to advocate for workers’ rights on a national stage. Notably, J.S. Woodsworth, who was arrested during the strike, became a founding member of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which evolved into the New Democratic Party (NDP) (Morley, 2006). This political shift marked a significant change in Canadian politics, as the CCF and later the NDP championed the causes of labour and social justice, continuing the legacy of the Winnipeg General Strike. In this way, the strike’s impact extended far beyond its immediate aftermath, influencing Canada’s labour relations and political movements for generations. More than a century later, despite it not being immediately successful, the Winnipeg General Strike is still considered one of the most significant events in Canadian working-class history.

One Big Union

The Winnipeg General Strike is the most visible demonstration of the discontent felt by workers post World War I. However, it was not the only action being taken. While there was a lack of agreement on how to improve conditions and standards of living amongst the working class and unionists, there was agreement that the current state of capitalism and attempts to suppress discontent through violence and criminalization would not be amendable. Just before the Winnipeg General Strike, a parallel movement with socialist roots was established further west. In Calgary, Alberta, in March 1919 some 250 delegates of the TLC from the western provinces agreed to form One Big Union (OBU) and detached themselves from the most eastern-focused and conservative TLC and the American Federation of Labour (AFL) (Ross & Savage, 2023; Heron & Smith, 2020).

By comparison, OBU was more inclusive and radical than the TLC, advocating a more revolutionary approach to labour organizing and economic reform. The following excerpt from the OBU’s original constitution and bylaws summarizes their more socialist perspective on what was required to adjust the playing field between capital and labour.

Excerpt from the Constitution and Laws of One Big Union

“As with buyers and sellers of any commodity, there exists a struggle on the one hand of the buyer to buy as cheaply as possible, and, on the other, of the seller to sell for as much as possible, so with the buyers and sellers of labor power. In the struggle over the purchase and sale of labor power the buyers are always masters — the sellers always workers. From this fact arises the inevitable class struggle.

As industry develops and ownership becomes concentrated more and more into fewer hands ; as the control of the economic forces of society become more and more the sole property of imperialistic finance, it becomes apparent that the workers, in order to sell their labor power with any degree of success, must extend their forms of organization in accordance with changing industrial methods. Compelled to organize for self-defence, they are further compelled to educate themselves in preparation for the social change which economic developments will produce, whether they seek it or not.

The One Big Union, therefore, seeks to organize the wage worker, not according to craft, but according to industry; according to class and class needs, and calls upon all workers to organize irrespective of nationality, sex, or craft into a workers’ organization, so that they may be enabled to more successfully carry on the every-day fight over wages, hours of work, etc., and prepare themselves for the day when production for profit shall be replaced by production for use.”

(“One Big Union,” 2021)

Many of the leaders of the Winnipeg General Strike were also members of OBU and thus the two often go hand in hand. At its peak, OBU had up to 50,000 members (Hebdon & Brown, 2020), but less than a decade later, it had all but fizzled out. Regardless, these socialist ideals and the drive for change sparked by OBU led to more labour leaders winning political positions. Although not for benevolent purposes, employers and the government began offering limited benefits to workers, such as pensions (Heron & Smith, 2020).

The Wagner Act

In 1935, Senator Robert Wagner proposed new legislation in the United States to address some of the conflict experienced between workers and employers on the heels of the extreme economic challenges brought about by the Great Depression. President Franklin Roosevelt wanted to stimulate economic growth and saw reduced strikes and more favourable terms for workers as a possible solution (McQuarrie, 2014). The National Labour Relations Act, which was the official name of the legislation, moved away from previous legislation that did not compel employers to collectively bargain or recognize unions. Under the new act, the following legal protections were established:

- Workers had the right to form and join unions.

- Employers were required to bargain with certified unions selected by the majority of employees in a workplace.

- Unfair labour practices by employers were clearly defined.

- A National Labor Relations Board was established.

- The National Labour Board had the power to order remedies when employers violated labour law.

- Exclusivity to the union with the most votes to represent employees.

- Collective bargaining between employers and unions was encouraged.

While the Wagner Act was American legislation, the influence of U.S.-based unions and legal changes significantly impacted the labour movement in Canada. Some provinces, like Nova Scotia in 1937 (Hebdon, et al., 2020), quickly passed similar legislation that required employers to collectively bargain with certified unions. However, it was not until 1944 that a uniquely Canadian package offering Canadian workers and unions similar protections would be passed.

Order-In-Council PC 1003

The passing of Order-In-Council PC 1003 in Canada marked a pivotal moment in the development of modern labour legislation. Modelled after the Wagner Act in the United States, this piece of legislation laid the groundwork for the labour rights that workers in Canada benefit from today (McQuarrie, 2015). PC 1003 was introduced during World War II by Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s government as a response to the growing number of militant recognition strikes and the inadequacy of the existing Industrial Disputes Investigation Act to effectively manage labour unrest (Heron & Smith, 2020). The legislation was intended to create stability during economic uncertainty, particularly with the looming fear of a post-war economic downturn like what had been experienced after World War I.

PC 1003 established several key principles that have become the foundation of Canadian labour law. It granted workers the right to join unions and provided a formal certification process for unions, thereby legally recognizing their role in the workplace. The legislation also prohibited unfair labour practices and made collective bargaining compulsory following union certification. It introduced the requirement for compulsory conciliation before a strike or lockout could occur and mandated that no strikes or lockouts could happen during the life of an active collective agreement. Additionally, all collective agreements were required to include a grievance arbitration process, and it established the creation of a National Labour Relations Board to ensure oversight and enforcement of these new rights and procedures.

The legislation was initially intended as a wartime measure, but its principles were so foundational that the Liberal government extended it two years beyond the war’s end. However, despite these efforts, intense strikes continued to disrupt many industries. Recognizing the temporary measure’s uncertainty and the struggle between labour and capital was far from over; the government established the Industrial Relations and Disputes Investigation Act in 1948, which permanently enshrined the principles of PC 1003 into Canadian law. Although it began as federal legislation, by 1950, all provinces had adopted similar laws, forming the basis of Canada’s modern-day labour laws (Heron & Smith, 2020). This legislation stabilized labour relations at a critical time and positioned the government as a key player in the ongoing balance between workers’ rights and economic interests.

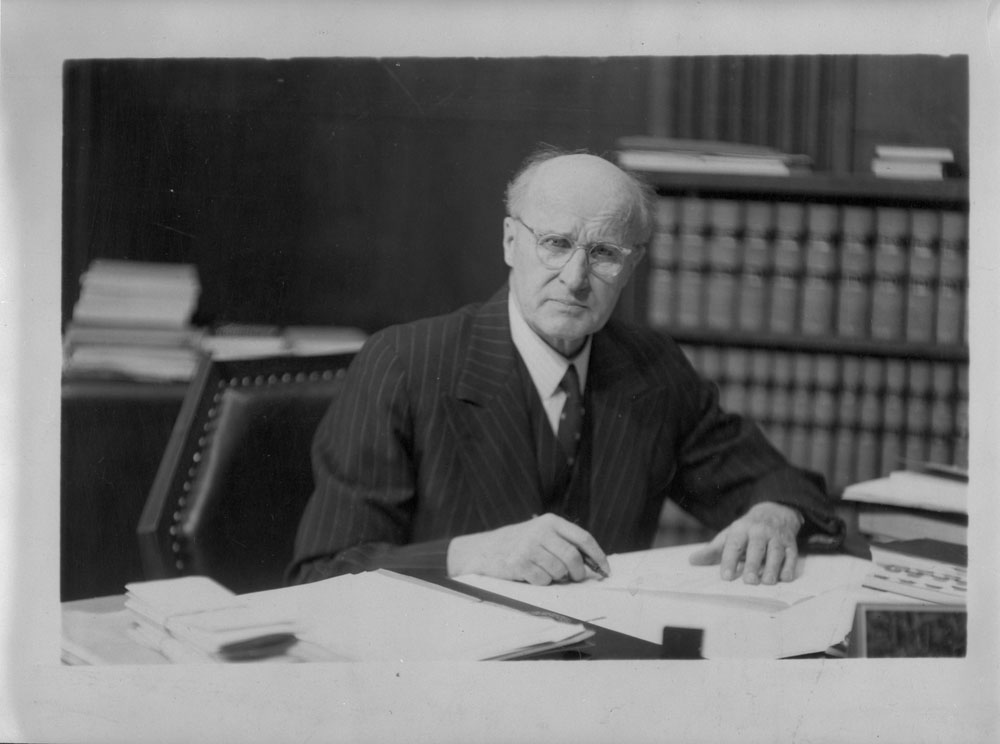

Windsor Ford Strike and The Rand Formula

Following WWII, concerns about downsizing and an economic downturn shifted the primary concern of industrial unions to union security (Heron & Smith, 2020; McQuarrie, 2014). While PC 1003 recognized certified unions as the bargaining agent for workers during negotiations in 1945, it was still a temporary measure. This issue came to a head in the first significant post-WWII strike at the Windsor, Ontario Ford Motor Plant. The International Union United Automobile, Aircraft and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (U.A.W.- C.I.O.) wanted a union shop whereby employees were required to join the union. The union was also looking for a system of automatic dues check-off where the employer would collect union dues from workers and remit them to the union. Under the system at the time, union leaders would have to collect dues from individual workers every month. This was a full-time endeavour with over ten thousand union-represented workers.

The strike lasted 99 days and involved 11,000 workers from the Ford Motor plant and 8,000 workers from other organizations who supported it (Panneton, 2006). The strikers picketed and used roadblocks to prevent anyone from accessing the plant, which caused Ford to move their corporate offices. In early November, a barricade covering 20 blocks around the plant brought parts of Windsor to a standstill, and the power plant that provided heat to the plant was shut down by UAW members. (“Where Did Our Rights Come From? The Rand Formula and the Struggle for Union Security,” 2013).

By the middle of December 1945, the UAW-CIO members voted to end the strike. The two parties agreed to binding arbitration to settle the issue of the union shop and automatic dues check-off. Justice Ivan C. Rand decided the case on January 29, 1946.

In his decision (Complete Rand Decision, 1946), Justice Rand articulated the two issues as follows:

“Union security is simply security in the maintenance of the strength and integrity of the union.

What is asked for is a union shop with a check-off. A union shop permits the employer to engage employees at large but requires that within a stated time after engagement they join the union or be dismissed if they do not. This is to be distinguished from what is known as a “closed shop” in which only a member of the union can be originally employed, which in turn means that the union becomes the source from which labour is obtained.

The “check-off” is simply the act by the employer of deducting from wages the amount of union dues payable by an employee member.”

While Justice Rand took no issue with union security and the need to ensure dues were paid and forwarded to the union by the employer, he issued a compromise on the matter of a union shop. He concluded that employees had a choice to join the union at the Windsor Ford plant, but all employees whose role fit within the bargaining unit would pay union dues. His rationale for this compromise was that regardless of membership in the union, all employees would benefit from the union’s efforts to negotiate improved wages and benefits. These dues were how the union could negotiate and administer the collective agreement (Dion, 2006). In the final decision, Justice Rand also required the union to avoid engaging in strike action during the life of the collective agreement and only after a secret ballot vote authorized by the Minister of Labour in Ontario (Complete Rand Decision, 1946).

The Rand Formula, as the decision was known, has been criticized in the years since. Opponents primarily object to using union dues to fund political campaigns; however, a Supreme Court of Canada decision in 1991 determined that this did not violate an individual’s freedom of association (Dion, 2006). By 1950, most collective agreements had adopted union security clauses based on the Rand decision (McQuarrie, 2014) and today, dues check-off is compulsory at the union’s request in most jurisdictions, including in the Canada Labour Code (Suffield & Gannon, 2015). The decision made by Justice Rand not only ended the contentious dispute at the Ford Motor Plant in 1946 but also created a system that allowed unions to ensure resources were available to support their members through collective bargaining, grievance arbitration and strikes or lockouts. Support that union members today still rely on to ensure fair treatment in the capitalist world that continues to thrive.

Media Attributions

- Figure 3.1 “Hamilton – Procession of Nine-Hour Movement Men” by Library and Archives Canada (1872), via the Government of Canada, is used under the Government of Canada Terms and Conditions.

- Figure 3.2 “1919-TALC-Canada” by Percy E. McDonald (1919), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 3.3 “Windsor – Ford strike – blockade on Sandwich Street East” by John H. Boyd (1945), via the City of Toronto Archives (Globe and Mail fonds, Fonds 1266, Item 99991), is in the public domain.

- Figure 3.4 “Ivan C. Rand” by Arthur Roy and Library and Archives Canada (1942–1948), via the Government of Canada, is used under the Government of Canada Terms and Conditions.

References

Boyd, J. H. (1945). Windsor – Ford strike – blockade on Sandwich Street East [Image]. City of Toronto Archives. https://gencat.eloquent-systems.com/city-of-toronto-archives-m-permalink.html?key=576602

Canadian Labour Congress. (n.d.). 1872: The fight for a shorter work-week. https://canadianlabour.ca/who-we-are/history/1872-the-fight-for-a-shorter-work-week/

Canadian Labour Congress. (2018, June 4). “One big union” founded in Calgary on June 4, 1919. https://canadianlabour.ca/one-big-union-founded-in-calgary-on-june-4-1919/

Cruikshank, D., & Kealey, G. S. (1987). Strikes in Canada, 1891-1950: Analysis. Labour/Le Travailleur, 20, 85–122. https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/llt20rr02

Dagger, R., & Ball, T. (2023, December 26). Socialism. Www.britannica.com. https://www.britannica.com/money/socialism

Fudge, Judy, & Glasbeek, Harry. (1994-1995). The Legacy of PC 1003. Canadian Labour & Employment Law Journal, 3, 357-400.

Hebdon, R., Brown, T. C., & Walsworth, S. (2020). Industrial relations in Canada (4th ed.). Nelson.

Heron, C., & Smith, C. W. (2020). The Canadian labour movement: A short history (4th ed.). Lorimer.

Kealey, G. S., & Gagnon, M. A. (2006, February 7). Trades and labor congress of Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/trades-and-labor-congress-of-canada

Library and Archives Canada. (1872). Hamilton – Procession of Nine-Hour Movement men [Image]. Government of Canada. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=2932698&lang=eng

McDonald. P. E. (1919). 1919-TALC-Canada [Image]. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1919-TALC-Canada.jpg

McQuarrie, F. (2015). Industrial relations in Canada (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Morley, J. T. (2006, February 6). Co-operative Commonwealth Federation. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/co-operative-commonwealth-federation

National Labor Relations Board. (2012). 1935 passage of the Wagner Act. nlrb.gov. https://www.nlrb.gov/about-nlrb/who-we-are/our-history/1935-passage-of-the-wagner-act

One Big Union. (2021, June 29). In Wikisource. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Constitution_and_laws_of_the_One_Big_Union

Palmer, B. D. (2006, February 7). Nine Hour Movement. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/nine-hour-movement

Public Service Alliance of Canada Prairie Region. (2013). Complete Rand Decision, 1946. https://old.prairies.psac.com/resources/complete-rand-decision-1946

Reilly, J. N. (2006, February 7). Winnipeg General Strike of 1919. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/winnipeg-general-strike

Ross, S., & Savage, L. (2023). Building a better world (4th ed.). Fernwood Publishing.

Roy, A. & Library and Archives Canada. (1942–1948). Ivan C. Rand [Image]. Government of Canada. http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=fonandcol&id=3220252&lang=eng

Suffield, L., & Gannon, G. L. (2015). Labour relations (4th ed.). Pearson Canada.

The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2024). Russian Revolution. In Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/Russian-Revolution

Thomson Reuters. (n.d.). Union Shop. https://ca.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/3-508-5479?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true

Unifor. (2013). Where did our rights come from? The rand formula and the struggle for union security. https://www.unifor.org/resources/our-resources/where-did-our-rights-come-rand-formula-and-struggle-union-security

William McKeown. (2017, September 14). Winnipeg General Strike [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/pVKo6xEgjaI?si=S0BmauHsqnerkWYS

social and economic doctrine that calls for public rather than private ownership or control of property and natural resources (Daggar & Ball, 2023)

Workplace where an employee, to retain his job, must join a union (representing the employer's workforce) within a certain time frame set by the employer and the union (Union Shop | Practical Law, 2024).