5 The Union Question

Why Employees Seek Union Representation

Melanie Reed

Learning Objectives

- Discuss theories on the formation of unions.

- Discuss the reasons workers might seek unionization.

- Differentiate between the different types of unions.

- Describe the structure of unions and the labour movement in Canada.

- Discuss union philosophy and how democracy is embedded in the Canadian labour movement.

“Her Toronto Bookstore Unionized in the Middle of a Pandemic. Now, She Hopes Others Will Join Her”

“With COVID-19 worsening work conditions, advocates say there’s no better time to unionize.

In the years leading up to the pandemic, Greta Whipple often wondered what would be the last straw that forced her to leave her part-time customer service job at Yorkdale shopping centre’s Indigo bookstore.

There were many things that frustrated her, including stagnant wages and the fear management could lay her off at any time. But she thought if she went somewhere else, things wouldn’t be any better.

“I can’t tell you the number of times … I contemplated a shift, but I really had the feeling that that would just be lateral,” said Whipple, 25. “You’re dealing with the same stuff under a different brand.”

Then came COVID-19. Whipple realized she no longer felt safe at work wearing insufficient PPE and running the risk of dealing with customers who refused to wear masks.

But instead of leaving, she helped spearhead the unionization effort at her store last summer, following in the footsteps of at least five other Indigo stores in Canada where employees unionized.”

Read the full story on CBC News

Source: Balintec, V. (2022, January 23). Her Toronto bookstore unionized in the middle of a pandemic. Now, she hopes others will join her. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/her-toronto-bookstore-unionized-in-the-middle-of-a-pandemic-now-she-hopes-others-will-join-her-1.6316016

Why Join A Union?

As the opening story illustrates, one of the most common reasons workers in Canada seek unionization is to improve their workplace conditions and wages. Recent research certainly supports the notion that employees represented by a union do enjoy better salaries and benefits. A recent study by Poirier and Stevens (2023) illustrates that the increase in wages earned by unionized workers in Canada ranges from 10.23% (average weekly) to 21.88% (median weekly). The report also shows that unionized workers across all industries have greater access to supplemental benefits, such as medical, dental, parental leave, pensions, and sick benefits. For unionized workers, the percentage of workers receiving these benefits ranges from 78% to 90%, and for non-unionized workers, it is 43% to 66% (Poirier & Stevens, 2023).

But is it just about wages and benefits? According to McQuarrie (2015), the factors that might cause someone to seek union representation can be summarized in four categories: personal, workplace, economic, and societal.

Personal Factors

In some circumstances, employees must join the union as a condition of employment. These closed-shop scenarios are common in Canada and do not leave the workers much choice if they prefer to remain non-unionized. In other circumstances, workers seek to form a union in their workplace or seek a unionized work setting outside of the desire for improvements in wages, benefits, and working conditions — what one might consider external factors or motivators.

One reason might be an alignment with a positive political affiliation or ideology toward unions. Perhaps a close family member or parent was a union member and spoke positively about the experience. Or maybe the opposite was true, and the individual formed a negative association with the benefits of being in a union. Either way, the messages we receive from our families and close friends can impact our view on whether unionization is beneficial. However, a positive view of unions usually will not translate into action unless the individual feels the union will better their situation. This utility function or instrumentality is an influential factor. If someone believes they can do better independently and that the union cannot affect the desired change, they are less likely to support a unionization effort (McQuarrie, 2015).

Similarly, coworkers and the industry someone belongs to may also influence an individual’s decision to be part of a union. If you and your coworkers are experiencing dissatisfaction in a normally unionized industry, you are more likely to seek union representation and vote favourably when the time comes. Of course, the opposite also impacts the likelihood of a certification vote. If workers feel they do not personally align with union principles of collective voice and negotiation, rewards for seniority, or democratic decision-making, they are less likely to support a unionization effort.

Workplace Factors

A lack of positive association with the workplace or an employee’s dissatisfaction with the organization is a primary factor for joining a union (Friedman et al., 2006) and the most commonly cited reason. Workplace factors are also the benefits of unionization that unions and labour organizations most frequently promote.

These factors include:

- monetary elements, such as wages and benefits (absolute and relative to others)

- working conditions

- job security

- occupational health and safety

- employee voice

- fair and equitable treatment

For example, on their website, the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), Canada’s largest private sector union, lists the following top ten benefits of joining a union.

Top 10 Union Advantages from CUPE

- Higher wages.

- Greater equality.

- Pensions/benefits.

- Job security and tenure.

- Health and safety.

- Predictable hours.

- Training and education.

- Transparency and equitable due process.

- Workplace democracy.

- Advocacy and political action.

For more details on each of these, visit the CUPE website

Source: Canadian Union of Public Employees. (2016, October 3). Top 10 union advantages. https://cupe.ca/top-10-union-advantages

Economic Factors

By the end of 2023, many popular media outlets declared the preceding year to be a remarkable one for unions and labour action (Bruce, 2023; Moscrop, 2023; Vescera, 2023; Waddell, 2024). Although union density did not significantly increase across Canada, there was clear evidence of heightened union activity: the number and duration of strikes rose, the length of union contracts extended, and, most notably for workers, negotiated wages increased (Bruce, 2023). The most frequently cited reason for these changes was economic factors.

Following the COVID-19 pandemic that began in 2020, many workers, like the protagonist in our introductory news story, had a different perspective on work and felt motivated to voice their concerns (Waddell, 2024). Issues such as workplace safety and paid leave for illness gained prominence. However, as businesses reopened and employees returned to the ‘office,’ two key economic factors emerged that spurred substantial worker action: a tight labour market and high inflation. These conditions created ideal scenarios for union and worker bargaining. Workers’ bargaining power naturally increases in a tight labour market where they are in high demand.

Typically, low unemployment rates deter unionization, as workers can more easily find new roles if dissatisfied with their current positions. Yet others suggest that low unemployment increases worker power, and thus, they will seize the opportunity to maximize the gains union representation can offer (Vescera, 2023). Even though unionization rates did not rise across the board, there was a noticeable increase in workers’ willingness to negotiate assertively with employers. Inflation, however, presents a different dynamic. In 2023, most Canadians found their money did not stretch as far for necessities, dining, and entertainment (Bruce, 2023; Vescera, 2023). Rising inflation generally pushes more workers toward unionization, seeking collective bargaining power to protect their purchasing power.

Societal Factors

As you have learned by studying some of the history of labour relations in Canada, many unions also improved living and work conditions for all workers, including those not represented by a union. In some cases, this meant protesting government or employer action, and in others, it meant involvement in politics to bring about change by proposing and implementing new laws.

For example, in August of 1940, after facing pressure and lobbying from unions, the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (now the NDP), and other social groups, the federal government created a national unemployment insurance program (Canadian Labour Congress, 2018). Although it protected less than half of workers at the time and has been curtailed and revised by many governments since, employment insurance (EI) remains a fundamental protection for all Canadian workers.

Today, labour legislation has a significant impact on levels of unionization. Provincial and federal labour codes dictate the process and level of demonstrated support required to secure union representation in a workplace. In 2022, under the John Horgan NDP government, the province of British Columbia amended its labour code to allow automatic certification if 55% of workers sign union membership cards. This process, known as single-step certification, is also possible in three other provinces and federally regulated workplaces (British Columbia Ministry of Labour, 2022). In BC alone, this one legislative change resulted in more than double the applications for certification in 2023 over 2022 (Vescera, 2023).

In addition to legislation, societal attitudes toward unions can influence workers’ willingness to seek representation. When a society consistently elects labour-friendly governments that support legislation strengthening worker and union rights, unions are generally viewed more favourably. For instance, in 2024, the federal Liberal government unanimously passed anti-scab legislation for the federal public service (Wilson, 2024). While the unanimous support for Bill C-58 from all three major political parties could be seen as a political maneuver, it may also indicate that the voices of Canadian workers are being heard following a year marked by increased labour action (Vescera, 2023).

Apply Your Learning

Re-read the opening vignette about Greta Whipple and her decision to seek unionization at the Toronto bookstore. Using the four factors described above, how would you classify her reasons for seeking unionization? What evidence supports your classification?

Union Formation Theories

Individuals or groups of employees may seek union representation for various reasons. Historically, researchers, such as Sidney and Beatrice Webb and Selig Perlman, attributed union organizing to the separation of labour and capital during the industrial revolution. They believed that the tipping point was the transition from a craft model of employment — where the workers also owned the business — to the industrial model — where workers sold their labour to more powerful capitalists. Other early theorists, like Perlman’s professor, John Commons, believed that unions were inspired by the competitive markets created by industrialization.

All three of these early theories contemplated the root causes that sparked the formation of unions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although these academics and writers have been gone for a long time, the premise of their thinking remains relevant today.

Sidney & Beatrice Webb

Sidney and Beatrice Webb were prominent social economists and writers who contributed significantly to the understanding of labour relations and the experiences of the working class in Victorian England. As founders of the London School of Economics and key figures in the Fabian Society, the Webbs were deeply concerned with social justice and the economic conditions of the poor (Cole, n.d.). Married in 1892, they co-authored many influential publications, including Industrial Democracy (1897), a result of six years of meticulous research on the functions and operations of trade unions in the UK (Webb & Webb, 1897).

The Webbs’ research led them to the conclusion that the division between labour and capital was a key driver in the formation of unions. They argued that the tendency of profit-focused business owners to exploit workers created a need for unions to serve as a counterbalance (McQuarrie, 2015). The Webbs identified three primary methods through which unions sought to address this imbalance:

- Mutual insurance involved unions collecting dues from their members to provide financial support during times of sickness, injury, or unemployment. These funds were also used to assist workers when factories closed or if they lost tools essential for their work, offering a form of security and stability that was otherwise lacking.

- Collective bargaining referred to unions negotiating with employers on behalf of their members to secure better terms and conditions of employment.

- Legal enactment involved unions lobbying the government to establish laws that set basic minimum employment standards for all workers, thereby aiming to ensure fair treatment across the board. (Webb & Webb, 1897)

By documenting these methods, the Webbs highlighted the crucial role of trade unions in advocating for workers’ rights and bridging the gap between the interests of labour and capital. While the Webbs identified these methods well over a century ago, they continue to be fundamental functions of trade unions today.

Selig Perlman

Selig Perlman was a labour historian born in Bialystok, Poland, then part of Czarist Russia (Witte, 1960). He immigrated to the United States in 1908 to study under John R. Commons at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Perlman became Commons’ research assistant and remained at this renowned institution, known for its focus on labour and unionism, until his retirement. His most famous work, A Theory of the Labor Movement (1928), offers a distinct perspective on the origins and role of trade unions (Witte, 1960).

Like Sidney and Beatrice Webb, Perlman believed that unions emerged as a response to the capitalist system. However, he developed his theories within the context of the United States, shifting from initially Marxist and Socialist viewpoints to new ideas about labour relations. Perlman argued that for unions to be successful, they needed to respect the basic principles of capitalism and private property rather than seek to overthrow the system (McQuarrie, 2014). He believed that unions and workers should aim to find ways to regulate capitalism effectively, aligning more closely with the American Federation of Labor’s view of craft unionism (Craig, 1990).

Perlman introduced the concept of “collective mastery,” suggesting that unions should focus on gaining control over job opportunities and collective bargaining rather than attempting to take over the capitalist system (Craig, 1990). He emphasized that unions needed the support of the middle class to thrive but should not be dominated by them. Central to Perlman’s theory was the “psychology of the labourer” (McQuarrie, 2015) or what he termed the “manualist mentality” (Craig, 1990). This concept is based on the idea that only workers genuinely understand the scarcity of work and, therefore, seek union representation to help control access to limited job opportunities and ensure job security.

Unlike the Webbs, who saw unions as agents for broader social change, Perlman believed that unions should concentrate on the immediate needs of their members, such as better wages and working conditions, rather than promoting large-scale social transformations. His theories reflect a pragmatic approach to labour relations, emphasizing the importance of unions working within the capitalist framework to achieve their objectives.

John R. Commons

Like his student Perlman, John R. Commons came to the Wisconsin school in the early 20th century (1904) and became an influential contributor to labour history and economics. Like the Webbs in the UK, Commons studied the changing work conditions in the United States better to understand the formation and development of trade unions. However, unlike his contemporaries, Commons believed that the emergence of the labour movement was rooted in the ever-increasing growth of competitive markets (Craig, 1990). In his popular article titled “The American Shoemakers” and later his volumes of “History of Labour in the United States,” Commons points to external factors of expansion and market growth as the source of these budding new organizations (Hunting, 2003).

Commons did not discount the separation of labour and capital and the industrialization of work as factors in the birth of the American labour movement. Still, he did emphasize that growth in competitive markets and the subsequent development of transportation and communication networks significantly impacted the U.S. (Craig, 1990). As capitalists expanded their operations into new markets, they felt a need to be as competitive as possible, which drove less ethical practices regarding workers. Thus, worker organizations formed to combat what Commons referred to as the “competitive menace” (Hunting, 2003). According to McQuarrie (2015), Commons saw a role for unions to “take the wages out of competition” by organizing workers in specific industries and ensuring their employers were competitive because of producing a quality product rather than becoming the lowest cost producer. Of course, expanding business into new markets also meant that unions could use the same networks for transportation and communication to expand their union organizing efforts (McQuarrie, 2015).

Union Function Theories

Although many scholars and thinkers in the early 20th century contemplated what brought the “union problem” to the forefront of society, others turned their minds toward the myriad ways that unions function and operate. While many agreed that industrialization was a driving force for many unions and labour organizations to form, there was less agreement that unions were homogenous and all operated within a standard structure. Much of the early thinking on unions, such as the viewpoint of Robert F. Hoxie, was that unions were both structurally and functionally diverse (Hoxie, 1914).

Robert F. Hoxie

Robert F. Hoxie believed that unions arose from a group consciousness that manifested in group action to address the group’s particular needs (Craig, 1990; Hoxie, 1914). Hoxie’s most significant contribution to theories of labour relations in the early 1900s was his perspective on how unions took action, which he articulated into a typology of union functions. He believed that unions did not operate with a single purpose but rather had multiple functional types that might arise depending on circumstances. In his article, “Trade Unionism in the United States,” Hoxie (1914) says that:

…unionism has not a single genesis, but that it has made its appearance, time after time, independently, wherever in the modern industrial era a group of workers, large or small, has developed a strong internal consciousness of common interests. It shows, moreover, that each union and each union group has undergone a constant process of change or development, functionally and structurally, responding apparently to the group psychology and therefore to the changing conditions, needs, and problems, of its membership. In short, it reveals trade unionism as above all else essentially an opportunistic, a pragmatic phenomenon.

Hoxie identified four functional types of unions: business unionism, friendly or uplifting unionism, revolutionary unionism, and predatory unionism (Hoxie, 1914). While these types differ in their purpose and means of achieving this purpose, Hoxie recognized that a single labour union could perform multiple functions and that switching between them depended on circumstance.

- Business Unionism is when a union predominantly functions to improve the working conditions of a specific workplace, trade, or industry. The focus is on a group of workers and negotiating the best possible outcomes through collective bargaining.

- Friendly or Uplifting Unionism is when a union prioritizes social interests and possibly the broader working class rather than the needs of a single group of workers or industry. Friendly unions engage in collective bargaining to achieve their goals but may also participate in political actions and work cooperatively with other organizations with similar aims (Craig, 1990).

- Revolutionary Unionism is a more radical form of unionism. This union function focuses on addressing class differences, often through political action but in some circumstances through sabotage, destruction of property, or acts of violence. According to McQuarrie (2015), Hoxie saw the purpose of revolutionary unionism as changing the class structure in society and gaining power for the working class. Some might suggest the blockade of vehicles around the Windsor Ford plant in 1945 was an act of revolutionary unionism by the United Auto Workers.

- Predatory Unionism is a form of unionism driven by a union’s desire to increase its power, often through illegal or, at the least, unethical means. Hoxie identified two types of predatory unionism that might manifest: hold-up and guerilla unionism (Craig, 1990).

- In hold-up unionism, the union increases its power by striking deals with employers that further their interests but do not benefit the workers they represent. This is often through sweetheart deals where the union accepts employers’ bribes to create more employer-friendly contracts.

- In guerilla unionism, the union operates directly against the employer rather than working in concert with them, often employing violence to further their aims (Craig, 1990). Today, we see evidence of a more tempered form of predatory unionism through union raiding. Although not illegal, trying to certify workers already represented by a union is seen as unethical by many unions and labour organizations in Canada, including the Canadian Labour Congress (Neumann, 2018).

E. White Baake

E. White Bakke was a professor at Yale University who played a crucial role in developing the fields of industrial relations and human resources in the 1930s and 40s (Encyclopedia.com, n.d.). He believed workers joined unions to improve their situation and reduce their frustrations by improving their standards of successful living (McQuarrie, 2015). At the core of his research was an element of instrumentality. If workers felt unions could help them live more successfully, they would support joining a union. However, if the opposite is true, they would avoid union representation (Craig, 1990). Bakke identified the following standards of successful living that his research indicated were sought by workers.

- Social status was the first goal that Bakke identified. Workers could obtain social status by being union members due to the democratic structure of unions and the opportunities they may have to secure roles within the bargaining unit or the union organization. This might include serving as a shop steward, serving as a member of the grievance or health and safety committee, or being elected to the role of bargaining until they become chair or obtain a position in the parent office of the union. Once someone is a leader in the union, they may also have opportunities to participate and lead other labour organizations like labour councils or labour federations, such as the Canadian Labour Congress.

- Creature comforts were also identified as goals employees might have when seeking unionization. Once certified as a bargaining unit, the first task will be negotiating a collective agreement. Through collective bargaining, workers can obtain the economic conditions and job security they most often seek when they unionize.

- Control is another function that unions provide workers. As you recall from The Legal Framework, the separation of labour and capital brought on by early industrialization removed much of the control workers had over their working conditions, living conditions, and choice in the type of work they pursued. Other theorists identified the creation of unions as a way to address this lack of control. Bakke believed that being part of a union helped employees gain control over their conditions primarily through collective bargaining. Bakke did note that if the union did not live up to the principles of democracy, some workers might feel they are trading control by management for control by the union and, thus, may be discouraged from being part of a union (Craig, 1990).

- Information sharing through educational programs, research, and news is another element Bakke identified as improving standards for unionized workers. Most large unions have research departments that provide members with information on the economy and society. For example, Unifor (n.d.c) has a section of its website dedicated to sharing its latest research. Unions also offer educational programs for their members to improve their opportunities to participate in the union locally and beyond. Training programs support union members in becoming part of collective bargaining teams, becoming shop stewards, or learning about union management. CUPE (n.d.b) has a catalogue of programs available to members across Canada.

- Integrity is the final factor Bakke identified. A union’s ability to offer integrity to workers is based on their perception. Can the union provide workers with “wholeness, self-respect, justice and fairness” (Craig, 1990)? If they believe that the union can offer this, they are more likely to say yes to joining.

Dunlop, Craig, & Systems Theory

In 1958, John T. Dunlop, a professor at Harvard University, published his pivotal work, Industrial Relations Systems (McQuarrie, 2015). In this book, Dunlops used a systems theory approach to create a framework for analyzing industrial relations. Dunlop’s model of the industrial relations system explained how unions function through their internal operating system but also within the context of the larger systems external to the union organization or a bargaining unit.

The premise of Dunlop’s model was that the three main actors (government, managers/employers, unions/workers) in the system acted based on different contexts (McQuarrie, 2015). These external environment contexts influenced the behaviour of the actors and the processes they would engage in.

Dunlop also identified a web of rules that governed the actions and interactions of these actors (McQuarrie, 2015). He identified processes for developing the rules to govern the interactions and the rules themselves. These rules might be organizational rules on employee conduct, wages, and performance measures, or they could also be laws that provide workers with fundamental rights and protections. Dunlop also identified procedural rules that outlined how the substantive rules would be applied. For example, the procedure employees must follow to request time off from work.

The following table adapted from McQuarrie (2015) captures the elements of Dunlop’s industrial relations system.

| Actors | Contexts | Web of Rules |

|---|---|---|

| Unions & Employees | Technologies | Procedures for Establishing Rules |

| Management & Employer | Markets & Budget | Substantive Rules |

| Government & Other Relevant Agencies | Power | Procedural Rules |

Note. Adapted from McQuarrie (2015).

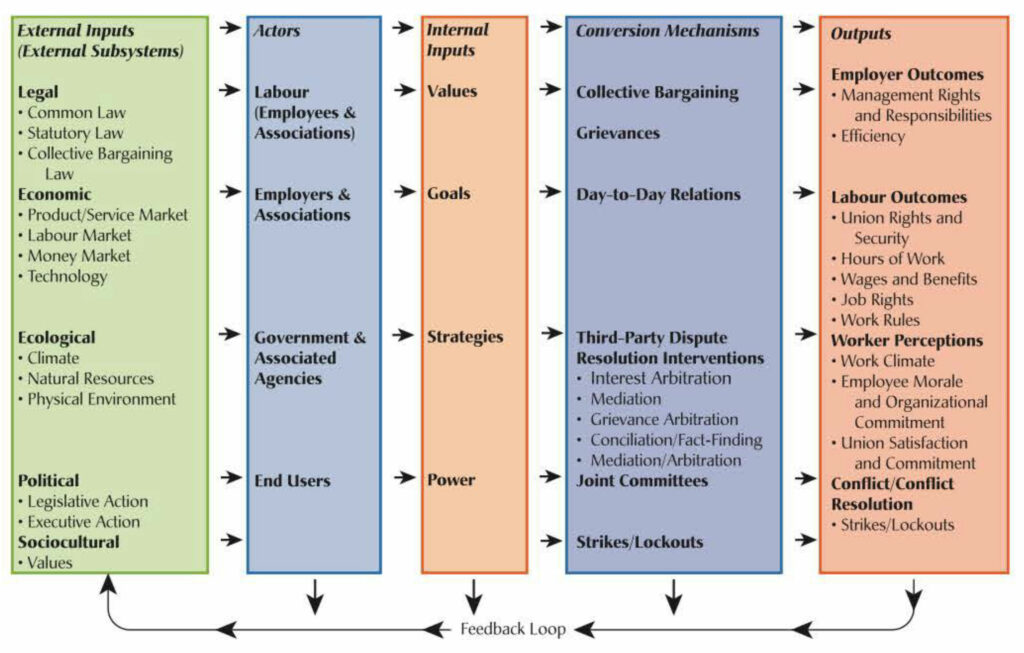

Canadian professor Alton W.J. Craig updated Dunlop’s framework using open-systems theory as a tool to analyze industrial relations (Craig, 1990). At its most basic, an open system receives inputs from the external environment, processes them, and creates a new output. A classic example is building a car. The auto manufacturer receives raw materials, such as component parts, and, using machinery and internal labour (actors), the parts are put together to create a new output that can be sold — a car.

Craig’s model added to Dunlop’s in a few specific ways. First, Craig clearly defined a set of external inputs or subsystems that impact the industrial relations system. This included the legal, economic, ecological, political, and sociocultural subsystems. Craig recognized the same three actors as Dunlop: government and other agencies, managers and employers, and unions and employees. Hebdon et al. (2020) added end-users as new actors in their rendition of the framework since the employment relationship impacts them.

Another one of Craig’s additions was internal inputs. He recognized that the actor’s values, goals, and strategies also impacted the system’s processes. For example, the union’s goals and management’s goals might not align. This could produce a conflict during collective bargaining, a possible conversion mechanism (process) that might be used in the system to create an output (a collective agreement). The relative power of each actor would also impact their ability to achieve their goals and was added to the framework as an internal input. The following diagram is Hebdon et al.’s (2016) version to illustrate these components.

As the above diagram illustrates, Craig added a feedback loop to reflect the open-system concept. This contribution represented the true nature of the industrial relations system. An output such as increased wages in a workplace or an industry could ultimately impact the external environment by affecting the economic subsystem. The conclusion of an arbitration would affect the legal subsystem by creating a precedent that future arbitrators might rely on.

While Craig (1990) did not suppose his work to be a theory of industrial relations, he hoped it would lead to the development of one. While further adaptations have not taken the framework to this level, it is a beneficial model for understanding how a workplace changes when unionization occurs. There are new laws and economic concerns; politics might have a more significant effect on the workplace, new actors are included along with their unique internal inputs, and the conversion mechanisms in the new employment relationship will be different.

Structure of the Canadian Labour Movement

Union Affiliations in Canada

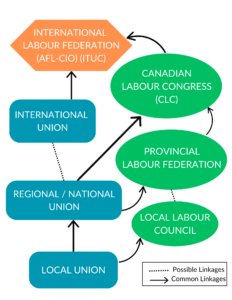

The structure of the Canadian labour movement is based on a series of relationships between and amongst unions and other organizations, commonly called affiliates. To be affiliated means to have a relationship with the organization, generally one of membership through payment of dues. For example, a local union in Kamloops, BC, might be a member of a local labour council like the Kamloops District Labour Council (KDLC) (n.d.). The local union would pay annual dues to the labour council, and in return, they could send members to KDLC events and meetings. Their members could also run for elections to be on the executive team at KDLC, and their particular issues or concerns could be brought forward to local politicians through lobbying and advocacy work of the council. This same opportunity and relationship exists through all the affiliate labour organizations illustrated in Figure 5.4. Look at each layer of this representation and the role of the various organizations in the labour movement in Canada.

Local Union

A local union represents the workers at a particular workplace or group of workplaces who come together to organize for collective bargaining and workplace representation. Local unions can either form independently or affiliate with an established union called the parent union. Typically, workers join an existing union due to its expertise, resources, and support. However, in certain circumstances, an independent union may be better positioned to represent the unique needs of its members, as is the case with athletic unions like the Canadian Football League Players Association (n.d.).

Local unions vary significantly in size and structure. They might encompass all workers across several workplaces, all workers performing the same type of work, or all workers at a single workplace, regardless of occupation — such as in a municipality or school district, which might have workers in various professions and roles in the same local. The structure depends on factors such as the potential number of union members, the number and proximity of workplaces, and the specific employment sector. There is no “typical” local union size — while some locals may have a large membership, others could consist of just a few employees.

The internal structure of a local union is grounded in democratic principles, ensuring member participation and representation. Local union members elect an executive body responsible for managing the union’s activities. The executive typically includes positions such as president, vice president, secretary, and treasurer (McQuarrie, 2015). There may also be roles on additional committees in larger locals, such as equity committees, joint occupational health and safety committees, or grievance committees. This democratic structure also ensures that all members can participate in and attend meetings and vote on union matters. Local decisions are usually made by way of a general membership meeting. If there is a parent union, the operation of the union is spelled out in the union constitution and bylaws (Ross & Savage, 2023) to ensure consistency and proper reporting and record keeping.

One of the critical roles in a local union is the shop stewards, who are union representatives within the workplace. Shop stewards assist members with grievances, advocate for them during disciplinary proceedings, distribute union literature, and welcome new members (McQuarrie, 2015). They are usually elected during annual elections and are crucial in maintaining a connection between the union’s leadership and general membership.

One of the most essential roles of shop stewards is to represent workers in investigation and grievance meetings. They are there as a witness to management action and inquiry and to speak on behalf of the employee and/or the union as necessary. In many collective agreements, management is required to invite the shop steward to attend any meeting that could result in any form of disciplinary action.

In larger unions, additional roles, such as business agents, may be necessary to manage day-to-day functions and assist the executive. These agents, who may serve multiple locals, often have significant responsibility and influence, particularly in contract negotiations and grievance handling. While most positions at the local level are unpaid, the business agent is generally a paid employee of the parent union. Individual locals may negotiate paid arrangements with their employer through collective bargaining, including a paid full or part-time position. While this may be more common in larger locals, a more typical arrangement is for individuals involved in union work or serving on the executive to have time away from their role with pay to conduct union business.

The union dues paid by members fund the local and other levels of the union, such as parent unions and affiliate memberships. According to McQuarrie (2015), local unions generally serve three main functions:

- dealing with workplace problems or grievances

- engaging in collective bargaining

- participating in political or social activities.

How these functions are carried out depends on the local’s membership, the guidance from business agents, and the level of member participation in votes and discussions.

Parent Union

Parent unions are larger bodies that oversee and support local unions. They may be referred to as regional, national, or international unions. Sometimes, a local union might be affiliated with multiple organizations, such as a regional office, a national parent, or an international union.

For example, the local municipal fire service where you live likely has members of the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF) (n.d.). That local would be affiliated with a provincial office, such as the BC Professional Fire Fighters Association (n.d.a), who would support them with a range of activities. That local would also be required to follow the constitution and bylaws of their parent union — the IAFF national office in Canada and their international office in the United States.

Regardless of the union’s structure, the parent union generally works closely with their locals and performs a number of supportive functions. Parent unions play a crucial role in creating and developing local unions, often dedicating employees or entire departments to union organizing efforts (Ross & Savage, 2023). They provide vital support to local unions’ ongoing activities, such as assisting with workplace issues, grievances, and arbitration processes. When it comes to collective bargaining, parent unions offer expert advice or help local unions hire professional negotiators, ensuring the local union maintains control while receiving the necessary training and guidance to effectively navigate negotiations. Beyond these functions, parent unions conduct educational programs to enhance members’ knowledge and skills, represent their members on broader labour councils, and engage in lobbying activities at the provincial or national level to advocate for workers’ rights.

Through these efforts, parent unions help strengthen the overall labour movement by empowering local unions and advocating for their interests on a larger scale. Below is a description of their role from the BC Professional Fire Fighters Association.

BC Professional Fire Fighters’ Association — What We Do

The BCPFFA is a service provider for its affiliates offering training and education in areas of provincial legislation, occupational health and safety, WorkSafe advocacy, financial assistance, bargaining, labour law, and advocacy for best practices in both public safety and fire fighter safety.

-

Work with the provincial government and WorkSafe BC to recognize and improve fire fighters’ health and safety for all of British Columbia’s professional fire fighters.

-

Assist with contract negotiation, grievance arbitrations and labour management issues.

-

Access to key information on wages, benefits and working conditions.

-

Provide online resources to address and assist with challenging issues facing affiliates and members.

-

Assistance in developing public and member communications.

-

Educate decision-makers about public safety and the importance of adequate staffing levels.

-

Provide financial assistance for small locals to attend educational training and conferences.

-

Provide locals with financial assistance for interest and grievance arbitrations.

-

Organize and facilitate health & safety, political, labour management and educational events & programs…

Source: BC Professional Fire Fighters Association. (n.d.b). What we do. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.bcpffa.net/whatwedo

Parent unions adhere to the same democratic principles as local unions. They are governed by an executive committee elected by representatives of local unions or regional offices. The parent union may have executive positions similar to those of the local union; however, they will often have some paid staff, including business agents. Elections and major decision-making in the parent union also happen through democratic processes through their convention or congress (McQuarrie, 2015). The parent unions’ constitution and bylaws will usually address how many delegates from each region or local can attend the convention and participate; generally speaking, each local can send one delegate to ensure larger locals do not have more voting power than smaller ones (McQuarrie, 2015). Like local unions, funding for parent unions comes from a portion of the union dues paid by members at the local level.

| Union | Membership in 2024 |

|---|---|

| Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) | 750,000 |

| National Union of Public and General Employees | 425,000 |

| Unifor | 315,000 |

| United Food and Commercial Workers Canada (UFCW) | 255,000 |

| United Steel, Paper and Forestry, Rubber, Manufacturing, Energy, Allied Industrial and Service Workers International Union (USW) | 255,000 |

| Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) | 180,000 |

| La Fédération de la santé et des services sociaux (FSSS) | 140,000 |

| Teamsters Canada (TC) | 125,000 |

| Service Employee International Union Canada | 100,000 |

Note. Created by the author

Labour Councils & Federations

You will see three green ovals on the right-hand side of Figure 5.4 above. These organizations are not unions but play a significant role in the Canadian labour movement. Labour councils and federations are often referred to as affiliate organizations because other labour organizations and unions will become members or affiliate with them.

These organizations primarily aim to support and advocate for workers and unions in Canada. While most of their affiliates are unions, their priorities and goals are not strictly focused on the interests of unions; rather, they represent the interests of all workers. Within Canada, there are three levels of affiliate labour organizations.

Labour Councils

Labour councils are smaller, more grassroots labour-focused organizations typically comprised of members of local unions. While smaller and more local, they play a significant role in supporting and advocating at the municipal level or within a geographic region with smaller communities. They provide an essential opportunity for local members to participate in advocacy and social, economic, and political change.

These councils are funded primarily through membership dues collected from their affiliated unions. Unlike larger unions or federations, labour councils often operate with limited financial resources due to their local focus and, as a result, typically do not have paid staff; instead, they rely on the efforts of volunteers who their members elect to carry out their activities (McQuarrie, 2015).

Local unions usually elect a representative to serve on the labour council they belong to, but affiliating with a labour council is not mandatory for all local unions. However, unions seeking membership in the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) must join a local labour council. Some unions, such as those under the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE) (2023), are required by their constitutions to maintain membership in their local labour councils.

Labour councils primarily focus on issues affecting workers within their region. Their activities may include showing solidarity with striking workers, lobbying local governments, and collaborating with other organizations to promote legislation that benefits workers and unions. Common issues of concern for labour councils include protecting healthcare services, advocating for minimum wage increases, and safeguarding funding for education. Additionally, some labour councils provide bursaries to the children of members in affiliated unions, further supporting the community’s needs (Kamloops & District Labour Council, 2024).

The following example is taken from the Calgary District Labour Council’s homepage, highlighting its focus in the fall of 2024.

Calgary District Labour Council’s — Focus

Today, the CDLC is working with our community partners to maintain and strengthen health care, the public education system, and to protect our social programs.

These things effect every person, union or non-union both working and unemployed. Labour activists volunteer their time in many aspects to build stronger and more caring communities. We do this by fighting for equal access to quality social programs, public services, decent jobs and improved standard of living for everyone.

Together, we are working to close the growing gap between the rich and poor in our society.

Source: Calgary & District Labour Council. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://thecdlc.ca/

Provincial Labour Federations

Provincial labour federations exist in all Canadian provinces. The Yukon Territory has its own federation, and the Northwest Territories and Nunavut have a combined federation called the Northern Territories Federation of Labour (n.d.). Most parent unions will be affiliated with the provincial labour federation in their province, as will labour councils. Since most work workers (union and non-union) in Canada fall under provincial labour and employment standards legislation, influencing the government at the provincial level is essential. Provincial labour federations will lobby provincial governments for changes that support workers and make it easier to certify unions.

The following example from the Saskatchewan Federation of Labour’s “About Us” page on their website outlines the broad role that a provincial labour federation can play.

Saskatchewan Federation of Labour — About Us

The Saskatchewan Federation of Labour represents over 100,000 members, from 37 national and international unions. Our affiliate membership belongs to over 500 locals across Saskatchewan and represents dozens of communities. We strive to improve working people’s lives throughout the province, whether organized or unorganized, and regardless of affiliation to the Federation. The SFL serves as Saskatchewan’s “voice of working people” in speaking on local, provincial, national, and even international issues. We support the principles of social unionism and struggle for social and economic justice for all.

Saskatchewan’s Labour Movement: The folks who brought you the constitutional right to strike!

Just some of the issues on which the Federation continues to provide advocacy include occupational health and safety, pensions, labour standards, the minimum wage, equal pay for women, and childcare. Of course, the SFL also plays a role on the national and international stage, participating in the debate on such issues as human rights, poverty, medicare, the growing gap between the rich and the poor, and homophobia, to name a few.

Source: Saskatchewan Federation of Labour. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://sfl.sk.ca/about

Canadian Labour Congress (CLC)

The Canadian Labour Congress (CLC) stands as Canada’s largest central labour federation, representing nearly 3 million workers nationwide (Canadian Labour Congress, n.d.b). Established in 1956 through a merger of the Trades and Labour Congress and the Canadian Congress of Labour, the CLC brought together various segments of the Canadian labour movement under one umbrella to enhance its capacity for collective action (Hebdon et al., 2020). The CLC is affiliated with provincial labour federations and many local labour councils, sharing a role and purpose similar to those bodies but operating nationally.

The CLC’s leadership lobbies the federal government on social and economic issues that impact all Canadians, advocating vigorously for workers’ rights. Beyond its advocacy work, the CLC offers substantial support and services to its affiliated unions and organizations. It assists with union organizing efforts, provides educational resources, conducts research, and communicates essential information regarding politics and legislation. Additionally, the CLC represents the Canadian labour movement internationally, ensuring that Canadian workers have a voice in global labour discussions.

The organization operates on democratic principles similar to those found within individual unions. Every three years, decisions about the CLC’s strategic direction are made at the CLC Convention, where delegates elect executive leadership. In 2023, Bea Bruske, formerly the vice-president of the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Canada National Council, one of the largest private sector unions in Canada, was elected for a second term as CLC President (Canadian Labour Congress, n.d.). Bruske is the second woman to hold the top role in the Canadian labour movement.

The CLC is funded through union dues collected from its affiliate unions and organizations, with a constitution that outlines the expectations for these affiliates. One notable feature of the CLC’s governance is its Code of Ethical Organizing, which guides how unions are expected to conduct themselves in organizing activities. A key principle of this code is that “affiliates should not organize or attempt to represent employees who are already organized and have an established collective bargaining relationship with another affiliate” (McQuarrie, 2015). This rule is designed to prevent ‘raiding,’ a practice where one union attempts to recruit members from another. The BC Nurses Union, for instance, was expelled from both the CLC and the BC Federation of Labour for such actions (McQuarrie, 2015). By discouraging raids, the CLC aims to promote the organization of workers who are not yet unionized and to minimize conflicts among its affiliates.

Other Labour Centrals in Canada

While the CLC is the dominate central labour organization in Canada, it is not the only one. The Confederation of Canadian Unions (CCU) (n.d.) has been operational in Canada since 1969. They are the largest national labour federation of independent unions and pride themselves on being “free of the influence of American-based international unions” (Confederation of Canadian Unions, n.d.). In 2024, they stated they had 20,000 affiliated member unions.

The province of Quebec also has three central labour federations in addition to the provincial Quebec Federation of Labour, which is a provincial affiliate of the CLC (Ross & Savage, 2023):

- The Confédération des syndicats nationaux (CSN) (Confederation of National Trade Unions) is the largest and represents 330,000 members and 1,600 unions as of 2024. (Confédération Des Syndicats Nationaux, n.d.)

- The Centrale de l’enseignement du Québec (Quebec Teachers’ Union), which began in 1974, is the next largest and represents 250,000 teachers and education workers in the province of Quebec as of 2024. (Centrale Des Syndicats Du Québec, 2024)

- The Centrale des syndicats démocratiques (CSD), which began in 1972, is the last one. The CSD stresses its mission is to represent unions seeking solidarity and autonomy. On their website, they state that their founding purpose was to represent “…workers who wanted a union movement that belonged to them and that was free from all political and financial ties.” (Centrale Des Syndicats Démocratiques, n.d.b)

Union Types

If you read Labour History: The Early Years, you learned about the earliest form of unionization in Canada: craft unions. According to Craig Heron (2014), craft unionism is a “form of labour organization developed to promote and defend the interests of skilled workers (variously known as artisans, mechanics, craftsmen and tradesmen).” Early industrialization threatened the craft model, as deskilling occurred with the rise of industrial unions in the early 20th century. Modern-day craft unions continue to adopt the same philosophy as their historic counterparts. They emphasize collective bargaining and supporting their members. According to Hebdon et al. (2020), the activities they engage in outside of collective bargaining focus on enhancing the “skill, training, and education of the craft or profession.”

An example of a craft union is the Kamloops Thompson Teachers’ Association (KTTA) (n.d.a), which is a union that represents 1,200 public school teachers in the Thompson-Nicola region of British Columbia. All the teachers in the KTTA are part of a larger federation called the BC Teachers’ Federation (BCTF) (n.d.), which represents 50,000 public school teachers. Their focus on supporting teachers and their collective bargaining is outlined in their mission statement below.

Kamloops Thompson Teachers’ Association — Mission

The Mission of the KTTA is:

- To promote the cause of education in the public schools of School District #73 (Kamloops-Thompson)

- To raise the status and promote the welfare of the teaching profession in the district of Kamloops-Thompson.

- To carry on such activities as may from time to time be ignited, prescribed or approved by the governing bodies of the Assocation or the British Columbia Teachers’ Federation.

- To represent its member and to regulate relations with their employer through collective bargaining of the terms and conditions of employment.

Source: Kamloops Thompson Teachers’ Association. (n.d.b). KTTA mission statement. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://ktta.ca/ktta-mission-statement

In contrast, industrial unionism, first heavily promoted in Canada through the arrival of the Knights of Labor in 1881, seeks to represent skilled and unskilled workers in various occupations. Most industrial unions tend to have a broader mandate beyond collective bargaining and advocate for societal reforms that benefit all working-class people (Hebdon et al., 2020). Many industrial unions might also be classified as social unions, as they engage in politics to improve the working conditions and lives of their members and all workers.

Examples of industrial unions in Canada include Unifor, the largest private-sector union in the country, and the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), an international private-sector union. On their websites, both unions highlight the social issues they campaign for, which include topics such as protecting reproductive rights, anti-racism, queer and trans rights, gender and equality, and food justice (Unifor, n.d.a; UFCW, n.d.b).

Business unionism, the type of unionism first promoted by Samuel F. Gompers and the American Federation of Labor and the Canadian Trades and Labour Congress (TLC), has an emphasis on enhancing the economic benefit of members while remaining politically neutral (Hebdon et al., 2020). Today, business unions may lobby the government and engage in politics in general but with an emphasis on increasing benefits and protections for unionized workers (Ross & Savage, 2023) rather than accomplishing large-scale social reforms.

Unions & Democracy

Canadian unions have typically operated within a culture of democracy (Lynk, 2000). Unlike U.S. labour law, the Canada Labour Code and provincial labour codes and acts do not have strict rules on union elections and the role of union officers (Lynk, 2002). Instead, union constitutions and bylaws generally outline the process for elections and the role and conduct of officers.

All the organizations outlined in Figure 5.4 elect officers from among their memberships and use voting through general meetings, congresses, and conventions for decision-making. At the local level, members engage in democratic decision-making when setting their agenda for collective bargaining and ratifying the collective agreement through a vote when negotiations conclude. If they cannot conclude bargaining and the union executive recommends a strike, the members are legally required to vote in favour of strike action. These actions not only create opportunities for participation in the union but, more importantly, give members a voice in the workplace and society they may not otherwise have.

Probably one of the most prominent and vital opportunities for participation and voice that the union offers workers is at the beginning of their relationship when they vote to be represented by a union. The certification process in all jurisdictions requires the workers to show their desire for union representation by signing cards and/or voting. So, from the very beginning of the relationship, democracy is a built-in element. According to Ross and Savage (2023), union democracy makes an essential promise to workers, “join the union, and you will have a meaningful voice in the union, in the workplace and in your community.” A promise Greta Whipple, the protagonist in our opening vignette, will likely welcome.

Apply Your Learning Answers

- Personal Factors — She is in an organization where other stores are starting to unionize.

- Workplace Factors — This is her primary reason for unionizing. She feels unsafe at work and is unhappy with her wages. You could also infer that her Managers were not addressing her concerns.

- Economic Factors — Greta refers to ‘stagnant wages,’ which are often the result of wages not keeping up with inflation.

Media Attributions

- Figure 5.1: “Inside a Chapters bookstore” by Pingping (2005), via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

- Figure 5.2: “Beatrice and Sidney Webb, c1895” by LSE Library (2013), via Flickr, is in the public domain.

- Figure 5.3: “Hebdon et al.’s Industrial Relations Systems Model” by Hebdon et al. (2020), Image courtesy of Top Hat, is used with permission under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

- Figure 5.4: “Union Affiliation in Canada” was created by the author under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

Angus Reid Institute. (2023, September 1). Labour Day: Union members boost the benefits of organized labour, but almost 40% say membership costs exceed gains. https://angusreid.org/unions-strike-labour-canada-ndp-conservatives-liberals/?ref=readthemaple.com

Balintec, V. (2022, January 23). Her Toronto bookstore unionized in the middle of a pandemic. Now, she hopes others will join her. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/toronto/her-toronto-bookstore-unionized-in-the-middle-of-a-pandemic-now-she-hopes-others-will-join-her-1.6316016

BC Professional Fire Fighters Association. (n.d.a). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.bcpffa.net/

BC Professional Fire Fighters Association. (n.d.b). What we do. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.bcpffa.net/whatwedo

BC Teachers’ Federation. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.bctf.ca/

British Columbia Ministry of Labour. (2022, April 6). Single-step certification will protect right to join a union. Government of British Columbia. https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2022LBR0006-000485

Bruce, G. (2023, December 28). Many workers hit the picket line in 2023. These 5 charts help contextualize a year of strikes. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/year-of-strike-2023-historic-1.7042081

Calgary & District Labour Council. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://thecdlc.ca/

Canadian Football League Players’ Association. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://cflpa.com/

Canadian Labour Congress. (n.d.a). Bea Bruske. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://canadianlabour.ca/who-we-are/officers/bea-bruske/

Canadian Labour Congress. (n.d.b). Who we are. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://canadianlabour.ca/who-we-are/

Canadian Labour Congress. (2018, August 5). Passage of the unemployment insurance act. https://canadianlabour.ca/passage-of-the-unemployment-insurance-act/

Canadian Union of Public Employees. (n.d.a). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://cupe.ca

Canadian Union of Public Employees (n.d.b). Union education. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://cupe.ca/unioneducation

Canadian Union of Public Employees. (2016, October 3). Top 10 union advantages. https://cupe.ca/top-10-union-advantages

Canadian Union of Public Employees. (2023). Constitution 2023. https://cupe.ca/sites/default/files/constitution_national_2023.pdf

Centrale Des Syndicats Démocratiques. (n.d.a). Home. Retrieved August 27, 2020, from https://www.csd.qc.ca/

Centrale Des Syndicats Démocratiques. (n.d.b). Mission de la CSD. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.csd.qc.ca/a-propos/mission-de-la-csd/

Centrale Des Syndicats du Québec. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.lacsq.org/

Cole, M. I. (n.d.). Sidney and Beatrice Webb. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sidney-and-Beatrice-Webb

Confédération Des Syndicats Nationaux. (n.d.). English Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.csn.qc.ca/en/

Confederation of Canadian Unions. (n.d.). About. Retrieved September 5, 2024, from https://ccu-csc.ca/about/

Craig, A. W. J. (1990). The system of industrial relations in Canada (3rd ed.). Prentice-Hall Canada Inc.

Encyclopedia.com. (n.d.). Bakke, E. Wight. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.encyclopedia.com/economics/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/bakke-e-wight

Fédération de la Santé et Des Services Sociaux. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://fsss.qc.ca/

Friedman, B. A., Abraham, S. E., & Thomas, R. K. (2005). Factors related to employees’ desire to join and leave unions. Industrial Relations, 45(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2006.00416.x

Hebdon, R., & Brown, T. (2016). Figure 1-1: Industrial relations systems model. In Industrial relations in Canada (3rd ed). Nelson.

Hebdon, R., Brown, T., & Walsworth, S. (2020). Industrial relations in Canada (4th ed). Nelson.

Heron, C. (2014, June 4). Craft unionism. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/craft-unionism#:~:text=Craft%20unions%20sought%20to%20maintain,to%20Canada’s%20first%20labour%20movement

Hoxie, R. F. (1914). Trade unionism in the United States: The essence of unionism and the interpretation of union types. Journal of Political Economy, 22(5), 464–481. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1819164

Hunting, J. D. (2003). John R. Commons’s industrial relations: Its development and relevance to a post-industrial society. Économie et Institutions, 2, 61–82. https://doi.org/10.4000/ei.722

International Association of Fire Fighters. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.iaff.org/

Kamloops & District Labour Council. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 6, 2024, from https://kdlc.ca/

Kamloops & District Labour Council. (2024). Bursaries. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://kdlc.ca/bursaries/

Kamloops Thompson Teachers’ Association. (n.d.a). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://ktta.ca/

Kamloops Thompson Teachers’ Association. (n.d.b). KTTA mission statement. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://ktta.ca/ktta-mission-statement

LSE Library. (2013). Beatrice & Sidney Webb, c1895 [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/lselibrary/9259293969

Lynk, M. (2000). Union democracy and the law in Canada. Journal of Labor Research, 21(1), 37–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-000-1003-6

McQuarrie, F. (2015). Industrial relations in Canada (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Moscrop, D. (2023, December 18). 2023 was a good year for Canadian labor. Jacobin. https://jacobin.com/2023/12/2023-canadian-labor-wins-unifor-autoworkers-automation-ai

National Union of Public and General Employees. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://nupge.ca/

Neumann, K. (2018, February 2). Union raiding is a blow to solidarity among workers. United Steelworkers Canada. https://usw.ca/union-raiding-is-a-blow-to-solidarity-among-workers/

Northern Territories Federation of Labour. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved June 23, 2022, from https://ntfl.ca/

Pingping. (2005). Inside a Chapters bookstore [Image]. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/pingping/28241876/

Poirier, A., & Stevens, A. (2023). The union advantage: A comparison of union and non-unionized wages in Canada and Saskatchewan. University of Regina. https://c0d1de.p3cdn1.secureserver.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Union-Advantage-Report-FINAL.pdf

Public Service Alliance of Canada. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://psacunion.ca/

Ross, S., & Savage, L. (2023). Building a better world (4th ed.). Fernwood Publishing.

Saskatchewan Federation of Labour. (n.d.). About us. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://sfl.sk.ca/about

Service Employees’ International Union. (n.d.). Who we are. Retrieved September 9, 2024, from https://www.seiuwest.ca/who_we_are

Teamsters Canada. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://teamsters.ca/

Unifor. (n.d.a). Campaigns. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.unifor.org/campaigns/

Unifor. (n.d.b). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.unifor.org/

Unifor. (n.d.c). Research Briefs. Retrieved September 30, 2021, from https://www.unifor.org/resources/research-briefs

United Food and Commercial Workers Union. (n.d.a). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.ufcw.ca/index.php?lang=en

United Food and Commercial Workers. (n.d.b). Issues. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://www.ufcw.ca/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=2215&Itemid=135&lang=en

United Steelworkers. (n.d.). Home. Retrieved September 12, 2024, from https://usw.ca

Vescera, Z. (2023, December 22). How 2023 became the year of unions. The Tyee. https://thetyee.ca/News/2023/12/22/How-2023-Became-Year-Of-Unions/

Waddell, D. (2024, January 2). Reinvigorated labour movement enjoys “remarkable year.” Windsor Star. https://windsorstar.com/news/local-news/reinvigorated-labour-movement-enjoys-remarkable-year

Webb, S., & Webb, B. (1897). Industrial democracy. Longmans, Green, and Co.

Wilson, J. (2024, June 24). Anti-scab legislation receives royal assent. Canadian HR Reporter. https://www.hrreporter.com/focus-areas/employment-law/anti-scab-legislation-receives-royal-assent/386939

Witte, E. E. (1960). Selig Perlman. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 13(3), 335–337. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2520300

Long Descriptions

Figure 5.3 Long Description: The table’s five columns are as follows:

- External Inputs (External Subsystems):

- Legal — Common law, statutory law, and labour law

- Economic — Product/service, labour market, money market, and technology

- Ecological — Climate, natural resources, and physical environment

- Political — Legislative action and executive action

- Sociocultural — Value

- Actors:

- Labour (employees and associations)

- Employers and associations

- Government and associated agencies

- End users

- Internal Inputs:

- Values

- Goals

- Strategies

- Power

- Conversion Mechanisms:

- Collective bargaining

- Grievances

- Day to day relations

- Third-party dispute resolution interventions — Interest arbitration, mediation, grievance arbitration, conciliation/fact-finding, and mediation/arbitration

- Joint committees

- Strikes/lockouts

- Outputs

- Employer outcomes — Management rights and responsibilities and efficiency

- Labour outcomes — Union rights and security, hours of work, wages and benefits, job rights, and work rules

- Worker perceptions — Work climate, employee morale and organizational commitment and union satisfaction and commitment

- Conflict/conflict resolution — strikes/lockouts

Every column, except for the last, has an arrow pointing to the next column. The latter four columns also have arrows pointing down to a horizontal arrow that leads back to the first column (External Inputs). These bottom arrows are labelled “Feedback.” [Return to Figure 5.3]

Figure 5.4 Long Description: The relationships between affiliate labour organizations is as follows (starting at the bottom):

- Local unions — Common linkages with regional/national unions and local labour council

- Regional/national unions — Common linkages with provincial labour federations and the Canadian Labour Congress; Possible linkages with international unions

- Local labour councils — Possible linkages with provincial labour federations

- Provincial labour federations — Common linkages with the Canadian Labour Congress

- International unions — Common linkages with the international labour federations (AFL-CIO and ITUC)

- Canadian Labour Congress — Common linkages with the international labour federations (AFL-CIO and ITUC)

- International labour federations (AFL-CIO and ITUC) are at the top of the chart

attempting to lure members from another union (rather than helping non-union workers join). (De, 2018)