3 Labour History in Canada: The Early Years

Melanie Reed

[Adapted from Rise of a Working Class from Canadian History: Post-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw, licensed under CC BY 4.0.]

Learning Objectives

- Describe the work and living conditions in Canada due to early industrialization.

- Explain the differences and similarities between craft guilds and early unions.

- Explain how industrialization and capitalism gave rise to Canada’s working class and a desire for union representation.

- Describe the early experiences of Indigenous Peoples in Canada with wage labour and unions.

Introduction

When we look around workplaces today and consider the laws and regulations that employers must follow, it is hard to imagine a time when none of those regulations existed. Take a moment and think about how your life would be different today if your employer could force you to work as many hours as they liked, fire you when you became ill, or require you to work in conditions that pose significant risks to your health. It is even more difficult to imagine children as young as nine years old working in dirty factories and mines under these same conditions.

With the onset of industrialization in Canada in the late 1800s, work shifted from a craft model to a more mechanized production model with a capitalistmaster-servant employment relationship . At the time, belonging to a union was also considered illegal, and the employment relationship was a party of two: employers and employees. But despite the disadvantage workers in Canada faced during the years of early industrialization, it was exactly these working conditions that motivated early industrial action and the formation of trade unions.

This chapter explains the conditions under which the working class formed in Canada as well as some key moments in the early days of the labour movement in Canada.

Craft Guilds — The First Unions

Before the industrial revolution, most production of goods was by craftspeople who created an entire product from start to finish. These skilled tradespeople usually owned their own business and created custom goods based on customer needs. In some situations, a craftsperson would commission the work of another craft if they lacked a particular skill or expertise, and they may have hired an apprentice to assist them.

However, all other aspects of making and selling a product were the responsibility of the craftsperson. This included marketing and delivering the finished product. Although this gave the business owner complete control over the work they did and how they created their product, they also assumed all the costs of production and the risks associated with operating their business. If a craftsperson became ill or injured, there was no one else available to do the work. There was also little time to work on their own skill development. (McQuarrie, p. 31).

The craft guilds, which began in North America in the 17th century, served to address the risks and limitations of the craft model of production. The following functions were typically associated with craft guilds:

1. Insurance Provider

One of the challenges with the craftsperson model was that it only worked if the craftsperson was healthy and well enough to work. One of the functions of the craft guilds was to provide a form of insurance to its members. In the same way that unemployment insurance and disability benefits protect today’s workers, this insurance function would provide a benefit to craftspeople who were unable to work due to illness or injury. The member of the guild would pay a fee and in return, they would receive benefits if they were unable to work. In some instances, the guilds might also provide a replacement worker.

2. Supply of Skilled Craftspeople

As guilds became more advanced, they played a role in controlling the supply of skilled labour. If someone wanted to learn a particular craft or trade, they would connect with the guild and could be placed with a journeyman to learn the trade or skill. This had the effect of ensuring a certain quality of product through the guild.

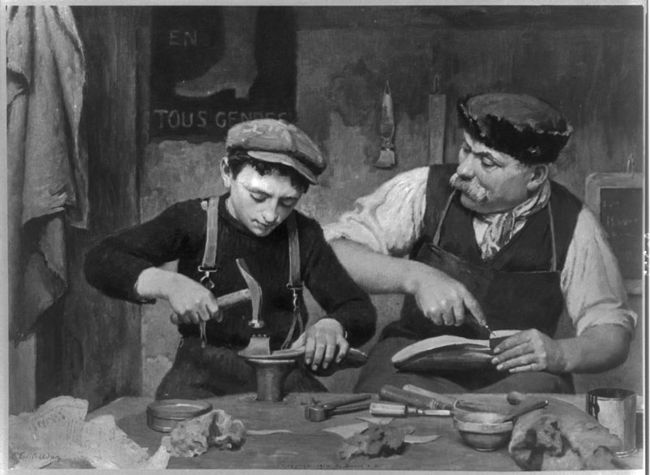

3. Apprenticeship & Training

Guilds also had exclusive control over the apprenticeship and education system. Individuals who were placed with a journeyman would be provided with training on their methods, processes, and trade secrets. They often lived with the journeyman and signed contracts for multiple years to learn the craft. Once the apprentice was able to prove their mastery of the craft, they would be declared a member in their own right and were permitted to operate their own business under the guild.

Even before industrialization took over, guilds began to recognize the opportunities provided by the division of labour and control of raw materials. The Wool Guilds in Italy were the first example of guilds transitioning from a collective of tradespeople, who produced unique goods and supported each other, to a master-servant employment relationship.

With a pool of craftspeople working to produce products and the guild being the only source of raw materials and the distributor of products, they effectively controlled the market. This resulted in lower wages for craftspeople, as they were paid a piecework rate of compensation, and the ability to produce more products faster.

By the 18th century, this model was prevalent in Europe and soon became the norm in North America. Soon, these merchant-capitalists were adopting machines and building factories as the industrial revolution began and forever changed how people work.

Rise of a Working Class

The Canadian working class was emerging well before 1867. By Confederation, one could say for the first time that the growth of the working class was now unstoppable. The creation of the Dominion of Canada took place precisely at that moment when widespread industrialization was visibly underway.

In 1851, fewer than a quarter of Hamilton, Ontario’s workers laboured in workshops of 10 or more employees; by 1871, the share was more than 80% (Palmer, 1992). In less than two decades, Hamilton had been transformed from a market town dominated by commerce into a powerful symbol of heavy industry. Though significant and startling at the time, this change was dwarfed by developments in the 1890s.

In that decade, Canadian economic growth simultaneously intensified in the older cities and found new fields in which to flourish in the West. The population of Canada in 1901 was 5,371,315; 10 years later it was 7,206,643 — an increase of 34%. At the same time, however, the labour force grew from 1,899,000 in 1901 to 2,809,000 in 1911, a phenomenal 50% increase (Statistics Canada, 1983). To put this into perspective, there were only 3,463,000 people in the Dominion in 1867 — by 1911, there were close to that many working, wage-earning Canadians. The working class were motivated and shaped by different factors in the various regions of the country, although common themes were quick to arise.

Workplace Conditions

A middle-aged factory worker in 1870 would likely remember very clearly working in settings where having a half-dozen other employees felt crowded. In the 1860s, working spaces were designed for small teams of mostly manual labourers and artisans. That was about to change.

Industrializing employers were finding their way in a new kind of business. Some came into it from their own smaller operations: small producers (some of them artisans) began employing more staff, mechanizing some processes, moving to larger spaces, and becoming manufacturers. This evolutionary model co-existed with instances where factory owners arrived ready-made from other parts of Canada but more often from the United States or the United Kingdom. Increased linkages across industries and systems also meant that capitalists and factory owners in one line of business regularly sought to close gaps in supply lines by means of vertical integration.

Along with innovations in the means of production and control over the supply chain, factory owners and capitalists introduced significant changes to work organization. Bringing workers under one larger roof and adding elements, like clocks, bells, and strict rules, created additional layers of control. With these rules also came consequences for not following them, which might include fines or beatings (Heron & Smith, 2020). Yet this early wave of industrialization did not completely eliminate the craft model in all industries. Craftspeople still maintained significant control over their labour in industries such as printing, cigarmaking, and shoemaking (Heron & Smith, 2020). It is in these skilled trades that the union movement in Canada began to take off.

Class Consciousness & Resistance

Studies of the birth of working classes identified two aspects in particular: the shared experiences of belonging to a population dependent on wage-labour in an industrializing economy and the awareness of the same. Loyalties cut across societies and cultures in many directions, muting the possibility of working people seeing themselves as members of a common socioeconomic category or class. One measure of that emerging and evolving class consciousness is the incidence of labour disruption in the 19th century.

The pre-Confederation era saw a rapid rise in labour disputes, accelerating in the 1860s. These principally involved small local associations of skilled craftsmen employed in factories. People of this generation could recall being independent craftsmen and transitioning into wage labour; now, they were facing the mechanization of processes and a consequent devaluation of their hard-earned skills. These workers were generally literate and aware of political and international events. They recognized that their struggles echoed those occurring in Britain and the United States. Every strike, in this context, was like a flare sent up from a ship in distress. Inevitably, others would respond.

By 1880, it is estimated that there were approximately 165 labour organizations in Canada, some local and many international. Virtually all of these were craft-based. As such, they perpetuated many of the associational rituals and practices from pre-industrial times. Marches, banners, oaths of loyalty, and the building of assembly halls were the most visible of these. Less obvious was the role that early unions played as social safety nets (Palmer, 1992, pp. 94-96).

Almost all had a “benevolent society” component to their work that involved life insurance for members’ families. The importance of this role could be seen when industrial accidents — most spectacularly in coal mining disasters — snuffed out lives a hundred at a time. Providing for widows and orphans was thus core to their mandate and an important part of building identification between labour and its community.

Coal mines and other resource-extraction industries in these years were a critical part of the pre-Great War economy. Providing fuel for steam power made coal important, but it was also key to heating food and urban homes, as cities and forest clearing had outstripped the ability of town people to find their own fuel.

Likewise, the food production industries of the late 19th century existed only because urbanites — the fastest growing demographic on the planet — could not address their own food supply. The grain economy boom of the turn of the century was part of this and so, too, was the growth of canneries. These appeared in fruit- and vegetable-growing regions, but they were most impressive in the fisheries. What these resource-extraction industries had in common, then, was a growing market that was certain to continue growing and, between 1867 and 1914, create a need for large numbers of labourers.

Wages and working conditions in factories, mines, and mills varied sharply according to race. Age was another factor. If the question was: Where do we find largely unskilled labour that will work under supervision in industrial conditions at rates that will profit employers? One answer was to find labour from a displaced or stressed peasant population. Another answer: from among the child population.

Childhood & Labour

Boys and girls had very different experiences in wage labour. Even in urban environments, girls’ labour was conceived of within certain gendered boundaries: domestic work, child-minding, and “fine-work” — textiles and stitchery — were likely destinations. However, girls’ work was comparatively undervalued, so the likelihood was always stronger that boys, rather than girls, would be sent out first to find wages for the household (Bradbury, 1990, pp. 71–96). Furthermore, female income levels were generally capped by expectations that they would become either dependents (in a male breadwinner model) or their income was little more than a supplement to the husband’s or father’s wage.

Boys, on the other hand, were part of a gendered culture of apprenticeships and the expectation that, with age and experience, their income levels would rise. Boys were welcomed into the workplace from the age of eight years until the late 1870s when social pressures and legislation began to push the acceptable starting age upward to approximately 12 years.

Child labour practices, in this respect, varied from province to province for two reasons:

- labour legislation was a provincial responsibility

- different industrial activities predominated across the country with practices being tailored to meet those local conditions

There was no consensus about a vision for childhood: whether children should be sent into often dangerous workplaces or into schools was one of several points of debate. Child labour legislation might protect working children from some hazards, but it also barred them from contributing to the household wage. As one study of children in mining observes:

Efforts to define children’s dependence clashed sharply with the working-class family wage economy, whereby boys and girls began to labour for wages at a young age as a key survival strategy. For this reason, working-class parents were among the principal opponents of legislation aimed to restrict children’s employment. (McIntosh, 2000, p. 40)

Some employers echoed these working-class qualms, principally because they saw child labour laws as a way of reducing profits by forcing the employers to hire more expensive adults. On the West Coast, restrictions on child labour chased the regulation of Asian labour and vice versa. The goal of a sufficient household wage among Euro-Canadian and Indigenous workers could be undercut by adult Chinese and Japanese labourers, who were willing to work for about the same amount as boys.

The racist context of debate on the issue of child labour was something of a distraction in that the English-speaking world was moving away from the use of children in industry. On the opposite coast, for example, and in the absence of a competing immigrant population, Nova Scotian collieries boys represented a falling share of an expanding workforce from 1866–1911, during which time their presence shrank from as much as 27% of the workforce underground (at Sydney Mines in 1886 and 1891) to as little as 5.5% in 1911 (at Springhill) (McIntosh, 2000, p. 71). The tide was turning against child labour.

The changing attitude around child labour is found throughout the 1889 Report of the Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital. Established in 1887, this was the eighth investigative enquiry into social, economic, and administrative issues. One study describes it this way: “The Royal Commission … is a testament to not only the turbulent economic relations in late-Victorian Canada, but the emergence of the Canadian state’s active role in social relations” (Cole, 2007). The Royal Commission’s recommendations — apart from the idea of an annual Labour Day — were mostly ignored by the federal government (which claimed that changes in labour conditions were rightly in the provincial jurisdiction), but its disclosures about child labour were widely covered in newspapers and aroused public concern. In the commissioners’ own words:

In some parts of the Dominion the employment of children of very tender years is still permitted. This injures the health, stunts the growth and prevents the proper education of such children, so that they cannot become healthy men and women or intelligent citizens. It is believed that the regular employment in mills, factories and mines of children less than 14 years of age should be strictly forbidden. Further, [we] think that young persons should not be required to work during the night at any time, nor before seven o’clock in the morning during the months of December, January, February and March. (Kealey, 1973, p. 13)

Under the ominous heading of “Child-Beating,” the commissioners made this recommendation:

The darkest pages in the testimony … are those recording the beating and imprisonment of children employed in factories. Your Commissioners earnestly hope that these barbarous practices may be removed, and such treatment made a penal offence, so that Canadians may no longer rest under the reproach that the lash and the dungeon are accompaniments of manufacturing industry in the Dominion. (Kealey, 1973, pp. 95–97)

Long hours were only one source of complaint among factory workers. Punishments abounded and were often arbitrary. Testimony from a 14 year old journeyman cigar maker in Montreal in 1887–1889 revealed a regime of arbitrary beatings (“a crack across the head with the fist”) when a job was done poorly and the possibility of being imprisoned in the factory in a “black hole,” a windowless room in the factory cellar, for up to seven hours at a time (Kealey, 1973, pp. 214–216). Adults might escape beatings but not fines; dismissals were not uncommon.

Moreover, involvement in a labour organization or a strike — particularly in a leadership capacity — could result in a worker’s name being added to a blacklist. Canada was large enough a country that a blacklisted worker might outrun this sanction, but sometimes the sanction followed them even into the United States. Civil suits were sometimes launched against labour activists, and many labour leaders spent some time behind bars. In the 20th century, as the size and distribution of industries and corporations increased, managers came to rely heavily on intelligence gathered by industrial spies.

Employers, at times, sympathized with some of the social goals of workers’ organizations (or unions) and began experimenting with what has come to be known as corporate welfarism. This is an array of services and benefits provided by the employer (but generally outside of a collective agreement). Employers did not, however, sympathize with the unions themselves and were often ruthless in disposing of the organizations and their supporters.

Class & Gender

Women were on the frontlines of industrialization and the creation of the working class. In 1901, 53% of all Canadian females were participating in the labour force, compared to 78.3% of all males (Statistics Canada, 1983). The labour of women was less visible than that of men in these years because of the persistence of cottage labour — or, in urban environments, “outwork.” Materials would be taken home by women workers and stitched together or in some other way refined so as to add value. This kind of labour (sometimes referred to as sweated labour could easily be as gruelling as any factory work. Women were employed for both types of work in Toronto in 1868, when the Globe newspaper reported that some 4,000 women were either factory workers or engaged in outwork (Palmer, 1992, p. 83).

Overall, the mechanization and systematization of work created more and more opportunities for women to engage in wage labour. The growing obsession of the 19th century state (federal and provincial) with surveying populations and businesses means that we have suggestive (if not comprehensive) information on the range of women’s experiences in the workforce.

Women’s wages were typically a fraction of men’s, regardless of sector. The 1889 Royal Commission on the Relations of Labor and Capital reported that women’s wages in Ontario were about one-third those earned by men. The assumption that a patriarchal breadwinner brought home the bulk of the household wage was widespread and difficult to dislodge (and, indeed, persists in some quarters today). Women’s wages were thus trivialized as top-ups or “pin money.”

As men’s wages lowered due to mechanization and increased competition for work that required fewer skills, the proportional contribution of women to the household economy became greater and greater. Children, too, were increasingly in demand in the industrial workforce, even sometimes taking jobs that had otherwise been done by adult males.

In cities, like Montreal, living conditions were particularly bleak in the last 40 years of the century. Housing was of a poor quality and cramped; infant mortality rates were high, as were maternal mortality rates. Historian of the working-class, Brian Palmer (1992), describes these domestic situations as potentially dangerous ones for women:

The underside of the adaptive families of Victorian Canada is a history of husbands deserting wives, of brutality in which women and children suffered the presence and power of abusive men, and of males (and, occasionally, females) appropriating the paid and unpaid labour of their spouses and offspring as well as availing themselves of sexual access to those who, emotionally and physically, had few resources to resist. (Palmer, 1992, p. 101)

By the end of the century, something like one-in-every-eight wage earners was a woman. The “needle trades” were dominated by women, and textile towns saw industrialism effectively feminized. The systematization of cigar production allowed large numbers of boys, girls, and women to penetrate what was once an adult male enclave.

Women’s involvement in the labour force increased dramatically from 1891–1921. In an era when the population overall and the size of the labour force doubled, the number of gainfully employed women expanded even more rapidly. In the professions (which include teaching and nursing), the numbers leapt from fewer than 20,000 to nearly 93,000; clerical and sales workers exploded from 8,530 to just shy of 128,000. The category “operatives,” which mostly covers industrial workers, saw women’s involvement rise from 150,649 to 240,572. However, the number of women on farms was flat and, as a share of the population, that number was falling. The number of women listed as labourers fell from 1,049 to 441, but rebounded to 11,716 in 1931 — which suggests that the category’s definition was an issue (Statistics Canada, 1983).

One distinctive aspect of women’s work lives was the influence of reproduction on labour. That is, the raising of families. While boys would rise through a process of apprenticeship through journeyman to adult worker and would continue on that rarely-broken path until they retired or died, girls and women entered and withdrew from the workforce more intermittently. Girls’ labour in the late 19th century was more heavily regulated (most provincial legislation kept them out of the workforce for two years longer than boys), so they were more likely to get some formal education or take hidden work in domestic settings or outwork. If the household’s income improved, girls might be withdrawn from paid work in order to contribute more to the rearing of younger siblings — a strategy that would perhaps free up adult women in the household for wage-earning opportunities.

Bettina Bradbury’s (1990) studies of women in industrializing Montreal show wives’ participation in the workforce proceeding through life cycle stages. The highest levels of participation are likely to come before the arrival of children, dipping with the arrival of infants, and then dropping severely when the household contains children between one and 10 years of age. Participation rates recover and peak once again when at least one of the children passes the age of 11 years.

Historians have struggled to recover what class awareness and experience meant to women at this time (Palmer, 1992, p. 136). Statements of solidarity and a commitment to political and social reform were often tempered by the social conventions of the Victorian era. While women might have challenged some of those limitations, they perpetuated others. In some women’s union locals in Ontario in the 1880s and 1890s, the membership was so reluctant to take on “unfeminine” leadership roles that they requested the appointment of male organizers.

Associations like the Knights of Labor gave a high priority to what were considered at the time to be gender issues. It is safe to assume that these positions reflect the feelings of their female membership, as well as at least a considerable proportion of the male Knights. Historian of labour, Brian Palmer (1992), has commented on this phenomenon:

[The Knights] deplored the capitalist degradation of honest womanhood that resulted from exploiting women at the workplace; many took great offence at the coarse language, shared water closets (toilets) and intimate physical proximities that came with virtually all factory labour in Victorian Canada. Nor did the Order turn a blind eye to domestic violence and the ways in which men could take advantage of women sexually. Local assembly courts could try and convict members of the Knights of Labor for wife-beating, and the Ontario Order was a strong backer of the eventually successful campaign to enact seduction legislation. (Palmer, 1992, pp. 94–96)

What all of these studies reveal is that industrialism brought women and children along with men into the urban cauldron of change in the same era. Moreover, this constituted a perceived change in the long-standing rural and commercial way of doing things. Life courses changed, conditions of work were invented out of nothing, new anxieties replaced old, and there was — in this mesh of experiences — a realization that a new social class was emerging.

Summary of Work Structure Differences Pre- & Post-Industrial Revolution

As discussed above, there are several differences in how people engaged in work before and after the Industrial Revolution. Table 3.1 provides a summary of these differences. Considering the dramatic changes to the work and lifestyle of wage workers may help you better understand the discontent many felt at the time.

| Work Structure | Pre-Industrial Revolution | Post-Industrial Revolution |

|---|---|---|

| Work Location | Home or workshop in community | Factory in a city or urban centre |

| Work Division | Craftsperson responsible for entire production process | Employee works on an individual part of the production process |

| Work Training | Apprenticeship with an established craftsperson | Limited as tasks were specialized and simplified |

| Ownership of Business | Craftsperson owned their own business | Employer |

| Market for Goods | Local or regional | National or international |

| Types of Goods | Custom | Mass produced |

| Design and Control of Work | Designed by craftsperson or individual workers | Designed by employer or Manager |

Note. Adapted from McQuarrie (2015, p. 33)

Indigenous People & Wage Labour

Although Indigenous people’s involvement in the Canadian labour market and organized labour in the late 19th and early 20th century is often ignored, they played a significant role in early economic development. Like women and children, Indigenous people had (and still have) a unique context as wage labourers, as their experience is rooted in colonialism and racism (Fernandez & Silver, 2017).

Settler colonialism in British North America was a form of colonialism that was much more than dispossessing land. It was an intentional effort to eliminate Indigenous peoples’ societies and ways of life. Removal from the land, regardless of the methods, destroyed social life, political structures, community connections, and cultural practices (Camfield, 2019). Colonialism also meant the intentional removal of Indigenous peoples through laws that prohibited their cultural practices, forced them to live on reserves, and incarcerated their children in residential schools. The Indian Act of 1876 “disrupted Indigenous systems of governance, restricted access to legal support, and banned the formation of political organizations and cultural practices like potlatches and the Sun Dance” (Brant, 2020).

Traditionally, Indigenous societies survived on subsistence and gift economies (Mills & McCreary, 2021). With the rise of the capitalist economy, some Indigenous people attempted to combine a subsistence way of life with engagement in the labour market. For example, the Squamish people of British Columbia incorporated wage labour as part of their seasonal hunting and fishing migrations when sawmills began opening along their routes (Parnaby, 2006). However, as settler colonialism continued and resource extraction expanded, many found fewer subsistence opportunities. For example, the elimination of bison herds in the prairies in the late 1800s eliminated a way of life for many Indigenous people (Camfield, 2019). This inability to sustain a family and society on their land led many Indigenous peoples to seek wage labour as a means of survival (Camfield, 2019; Mills & McCreary, 2021).

Indigenous men, women, and some children across Canada engaged in wage labour around the turn of the century. They worked in industries requiring physical labour, such as fisheries, sawmills, mining, agriculture, textiles, manufacturing, railway constructions, cooking, and domestic workers (Fernandez & Silver, 2017). In Quebec, the Kahnawake Mohawk men worked for centuries in the fur trade, but in the late 1800s, they became known for their contribution to the ironwork and steelwork trade. They built bridges, helped build the Grand Truck Railway, and eventually played an instrumental role in constructing the New York skyline, as they developed expertise in high construction work (Fernandez & Silver, 2017; CBC Radio, 2022).

While the industries Indigenous people worked in across Canada varied, their position in the worker hierarchy was consistently low. Indigenous workers were paid the least and had the least security in the emerging capitalist system. As they balanced subsistence and cultural practices, they were often replaced by more vulnerable workers, like Chinese labourers and later by white European settlers who were more dependent on wage labour. As the European population in Canada grew, they became more favoured, eventually pushing Indigenous workers out of the paid labour force (Fernandez & Silver, 2017). Work opportunities were heavily racialized and gendered, with Indigenous women and children at the bottom of the hierarchy (Camfield, 2019; Fernandez & Silver, 2017).

Although rarely acknowledged in labour relations history, Indigenous workers were involved in early union activities. In 1906, Indigenous longshoremen started Local 526 of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) union and soon after engaged in labour action. Parnaby (2006) describes the IWW as a likely fit for the Squamish men who formed the local, as it was a union that “offered up a heady mix of revolution and reform to those workers who did not fit well into the established craft union structures” since they continued their seasonal practices. In British Columbia, Indigenous fishermen participated in multiple labour disputes along the Fraser River over the prices paid by the canneries (Ralston, 2006). The Kahnawake Mohawks also struck against their employer in 1907 during the construction of the Quebec Bridge, expressing safety concerns (Fagan, 2022). Tragically, their grievances went unheard, leading to one of the worst industrial accidents of the time, killing 76 people, including 33 Kahnawake men, when the bridge collapsed on August 29, 1907.

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.1: Apprenticeship [reproduction] by Louis Emile Adan (ca. 1914), via United States Library of Congress’s Print and Photographs division [Digital ID cph.3b27512] and Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

- Figure 2.2: Coal mining at Tofield – men working by John Woodruff (ca. 1900-1910), via Canada Department of Mines and Resources and Library and Archives Canada [Access No. 1939-458 NPC], is in the public domain.

- Figure 2.3: Young girl probably with bag of coal gathered from beside box cars by Unknown Photographer (ca. 1900), via Library and Archives Canada [Access No. 1975-069 NPC], is in the public domain.

- Figure 2.4: Women working on primers, [Canadian General Electric Co. Ltd., Peterboro, Ont by Canada Department of National Defence (1914-1918), via Library and Archives Canada [Access No. 964-114 NPC], is in the public domain.

- Figure 2.5: Mohawk Skywalkers constructing Rockefeller Center, 1928, photo Lewis Hine by Lewis Hine (1928), via Wikimedia Commons, is in the public domain.

References

Belshaw, J. D. (2016). Canadian history: Post-confederation. BCcampus. https://opentextbc.ca/postconfederation/

Bradbury, B. (1990). The family economy and work in an industrializing city: Montreal in the 1870s. In G. A. Stelter (Ed.), Cities and urbanization: Canadian historical perspectives (p. 141). Copp Clark Pitman.

Brant, J. (2020, May 1). Racial segregation of Indigenous peoples in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/racial-segregation-of-indigenous-peoples-in-canada

Cambridge Dictionary. (2022, November 9). Capitalist. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/capitalist

Camfield, D. (2019). Settler colonialism and labour studies in Canada: A preliminary exploration. Labour / Le Travail, 83, 147–172. https://doi.org/10.1353/llt.2019.0006

Canadian Labour Congress. (n.d.). This Week in Canadian Labour History. https://canadianlabour.ca/uncategorized/twlh-apr-3/#:~:text=On%20April%2018%2C%201872%2C%20the

CBC Radio. (2022, September 8). How Mohawk ironworkers from Kahnawake helped build New York’s skyline. CBC. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/how-mohawk-ironworkers-from-kahnawake-helped-build-new-york-s-skyline-1.6576316

Cole, S. J. (2007, December 17). Commissioning consent: An investigation of the Royal Commission on the relations of labour and capital, 1886-1889 [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Queen’s University. http://hdl.handle.net/1974/963

Fagan, S. (2022, June 3). Choreographer tells the little known story of Mohawk ironworkers lost in the Quebec Bridge Disaster. CBC Radio. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/quebec-bridge-disaster-kahnawake-first-nation-1.6476819

Fernandez, L., & Silver, J. (2017). Indigenous people, wage labour and trade uions: The historical experience in Canada. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

Heron, C., & Smith, C. W. (2020). The Canadian labour movement: A short history (4th ed.). Lorimer.

Kealey, G. S. (Ed.). (1973). Canada investigates industrialism: The royal commission on the relations of labor and capital (abridged). University of Toronto Press. (Originally work published 1889)

McIntosh, R. (2000). Boys in the pits: Child labour in coal mines. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

McQuarrie, F. (2015). Industrial relations in Canada (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Mills, S., & McCreary, T. (2021). Which side are you on? Indigenous peoples and Canada’s labour movement. In S. Ross & L. Savage (Eds.), Rethinking the politics of labour (2nd ed., pp. 133–150). Fernwood Publishing.

Palmer, B. D. (1992). Working class experience: Rethinking the history of Canadian labour, 1800-1991 (2nd ed.). McClelland & Stewart.

Parnaby, A. (2006). “The best men that ever worked the lumber”: Aboriginal Longshoremen on Burrard Inlet, BC, 1863-1939. Canadian Historical Review, 87(1), 53–78. https://doi-org.ezproxy.tru.ca/10.3138/CHR/87.1.53

Ralston, H. K. (2006, February 7). Fraser River fishermen’s strikes. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved July 1, 2024, from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/fraser-river-fishermens-strikes

Statistics Canada. (1983). Historical statistics of Canada (F. H. Leacy, Ed., 2nd ed., Catalogue No. CS11-516/1983E-PDF) [Tables]. Government of Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/pub?id=9.692518&sl=0

Attribution & Changelog

Rise of a Working Class from Canadian History: Post-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Changes:

- Created a new title more relevant to this collection

- Added a new introduction and section on Craft Guilds

- Added a paragraph to Working Conditions

- Added a section on Indigenous People and Wage Labour

- Removed some photos and added others more relevant to this collection

- Small sections of content from the section on Child Labour were removed

- Added a table outlining the differences between pre and post-industrial revolution workplaces

- Changed reference notes to in-text citations and full APA references in the Reference list as per APA style guide

An employment relationship in which employees have few rights (Hebdon et al., 2020).

someone who supports capitalism (= an economic and political system in which property, business, and industry are controlled by private owners rather than by the state, with the purpose of making a profit). (Cambridge Dictionary, 2022)

In economics and business, a system in which the whole or most of the supply chain is owned by the same individual(s) or firm. Early examples come from the steel industry which in some cases controlled the production of coking coal, the supply of iron ore, foundries, and railways that consumed the final product.

From: 3.4 Rise of a Working Class from Canadian History: Post-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

A way of measuring income that extends beyond the breadwinner model and incorporates incomes earned by every member of the household/family.

From: 3.4 Rise of a Working Class from Canadian History: Post-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Equates subsidies to corporations with social welfare paid to individuals. In 1972, NDP leader David Lewis coined the phrase “corporate welfare bums” as a way of identifying what he perceived as the hypocrisy of attacks on the poor by anti-welfare business leaders.

From: 3.4 Rise of a Working Class from Canadian History: Post-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Work that takes place over long hours; exhausting and generally poorly paid; very often involves "outwork", the taking home of materials that are assembled there, usually by female employees, who are paid on the basis of output.

From: 3.4 Rise of a Working Class from Canadian History: Post-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw, licensed under CC BY 4.0.