6 Union Certification

Melanie Reed

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the steps in the union organizing campaign.

- Discuss the union certification process.

- Analyze management actions during the union certification process.

Introduction

If a group of employees in a workplace decides to have a union represent their interests with the employer, they have the legal right to do so in all Canadian jurisdictions. Regardless of jurisdiction, all labour laws outline a process for union certification. These laws also identify each party’s expected conduct and role in this process — union, employer, and the relevant labour relations board. Unfair labour practices are more common during the union certification process than other interactions between the union and the employer (McQuarrie, 2015). This chapter will outline the stages of a union organizing campaign, the certification process, and how employers and the union can interfere in the employees’ private decisions to join a union by engaging in unfair labour practices.

Organizing Campaign

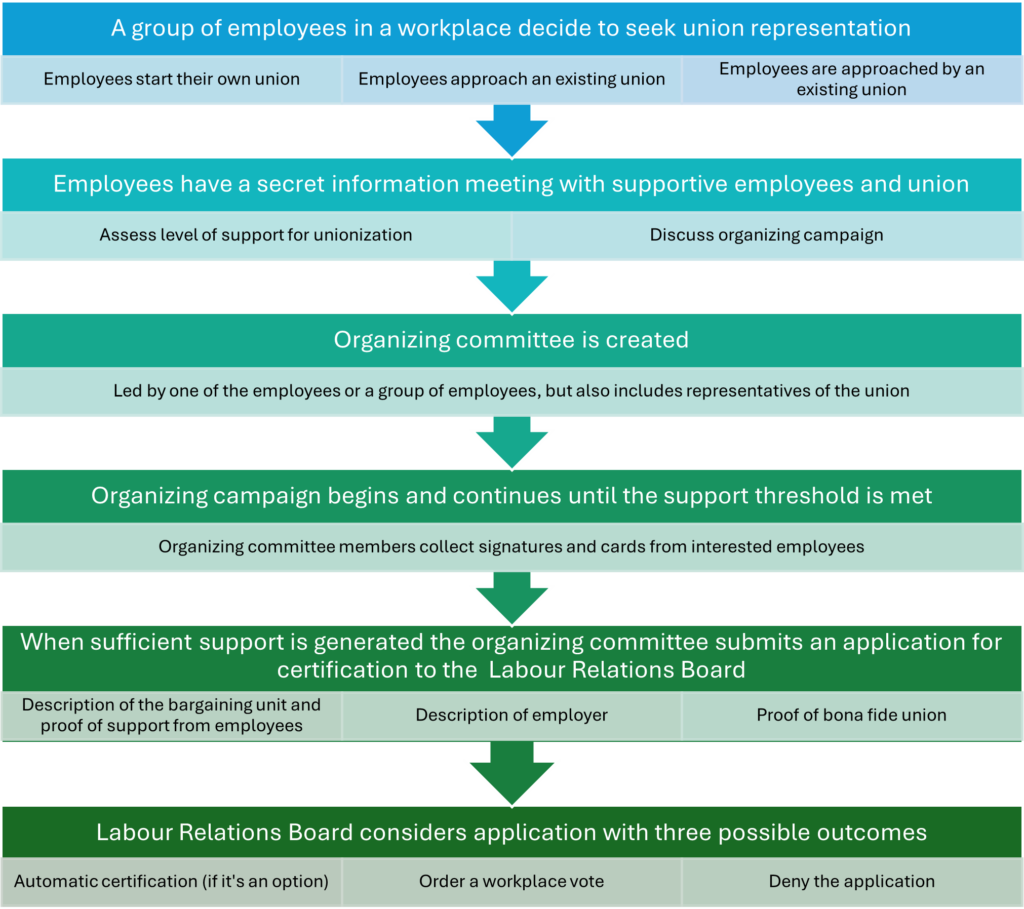

Once a group of employees in a workplace decides they are interested in union representation, the first stage of the process is called the organizing campaign. Unlike a political campaign, this campaign begins quietly within a group of employees known to support unionization. The organizing campaign aims to educate employees about the benefits of union representation and to collect evidence of employee support. Once sufficient support is demonstrated through signing cards, the campaign concludes with an application to the appropriate labour relations board (LRB) for union certification. Figure 6.1 below outlines the main steps of this campaign.

It is rare in Canada for workers to create an independent union if they desire union representation. More often, if a group of workers in a workplace discusses their desire to be represented, they will reach out to an existing union or labour federation for assistance. It is also common for unions to approach workers directly. Some unions develop campaigns to organize workers in specific industry sectors or workplaces with little or no union representation.

For example, in 2021, Teamsters in Canada developed a campaign to represent workers in Amazon warehouses. According to Love and Warburton (2021), the international union attempted to unionize nine facilities across the country, starting with a warehouse in Nisku, Alberta, where they required 40% of workers to sign cards to have a workplace vote. At the time, none of Amazon’s North American warehouses were unionized, and some attempts in the United States were unsuccessful. The Teamsters Union hoped they would have greater success with more favourable labour laws in Canada.

“Unionization votes in Canada do not have any direct bearing on the United States, but they could raise enthusiasm,” said John Logan, a labor professor at San Francisco State University.

“Organizing at a place like Amazon requires workers to take a certain amount of risk,” Logan said. “If they can look to other places and see that that risk has paid off for other workers, then they are far more inclined to do it themselves.”

Union members are going to great lengths to connect with Amazon workers, sleeping in their cars to catch the employees after graveyard shifts and forging ties at local churches. (Love & Warburton, 2021)”

Many unions and labour organizations will have a page on their website dedicated to union organizing. Here, they will explain the certification process and the benefits of joining the union and, in some instances, include information about their current organizing campaigns. Many unions also create videos to promote their union and organizing efforts. Below is an example of this style of video from the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC).

Source: PSAC-AFPC. (2022, May 30). Organizing for change // En avant pour le changement [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/lwj1wQTHLv8?si=ybm4kMj-UhMf1xqk

If you are using a printed copy, you can scan the QR code with your digital device to go directly to the video: Organizing for change

Information Meeting

Once even a small group of employees has connected with a union, the organizing campaign will begin with an information meeting. This is an opportunity for the union to discuss employees’ concerns, explain what the union can offer, and explain the certification process. This meeting usually involves a limited number of employees who support unionization.

At this stage, most people in the workplace will not be aware that discussions with the union are taking place. This initial meeting happens during non-working hours and away from the workplace. Sometimes, the union will rent a meeting room in a hotel or restaurant or the group will meet at an employee’s home. The purpose of keeping this meeting secret is not to alert management or non-supportive employees that an organizing campaign is underway. This prevents the employer from engaging in unfair labour practices, such as terminating or disciplining known union organizers, and prevents employees who do not support the effort from leaking information about the campaign to the employer.

Organizing Committee

If the union representatives believe there is a good chance of union certification, they will encourage the interested employees to form an organizing committee. This committee is usually made up of employees who are supportive of the union and knowledgeable about the workplace. A union representative may join the committee, but the employees will lead the campaign and discuss unionization with their co-workers. According to McQuarrie (2015), there are two main reasons for this:

- Employees will have more credibility within the workplace.

- Employees will be knowledgeable about workplace issues and employee concerns.

Access to employees within the organization is also a factor. Unions and employees are prohibited under labour law to solicit support for the union during working hours. Therefore, employees must engage with their co-workers outside the workplace or on breaks. The union is also not permitted to enter the workplace.

The primary purpose of this campaign is to encourage employees to show their support for union representation by signing a card or petition. The committee is attempting to reach the support threshold in their jurisdiction, which will allow them to apply for certification to the relevant labour relations board. This threshold varies by jurisdiction but is generally between 40% to 60% of employees.

In some jurisdictions, employees must also pay a small amount of money to show their support for the union. If the union is not certified as the bargaining unit, the money will be returned to the employees, and if it is successful, the funds will be put towards their union dues. For example, under federal jurisdiction, employees show their support for union representation by signing a card and paying $5 to the union (see Canada Industrial Relations Board’s (n.d.a) page on labour relations certification).

The following table is from The Legal Framework chapter and provides links to all the provincial labour laws. These laws outline the certification process in each jurisdiction and the required level of support to apply for certification.

| Province | Name of Labour Relations Law |

|---|---|

| British Columbia | Labour Relations Code (1996) |

| Alberta | Labour Relations Code (2000) |

| Saskatchewan | Saskatchewan Employment Act (2013) |

| Manitoba | Labour Relations Act (1987) |

| Ontario | Labour Relations Act (1995) |

| Quebec | Labour Code/Code du Travail (1996) |

| New Brunswick | Industrial Relations Act (1973) |

| Nova Scotia | Trade Union Act (1989) |

| Prince Edward Island | Labour Act (1996) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | Labour Relations Act (1990) |

Application for Certification

Once the employees and the union believe they have achieved the required threshold of support through card signing or a petition, they prepare the application for certification. This application must clearly identify three pieces of information:

- The employees who will be certified as a bargaining unit.

- The employer of these employees.

- The union that will represent these employees.

The union must also include the cards or petitions with signatures from employees who support unionization, as the labour relations board (LRB) will verify these. Once all the required information is collected, the application for certification is submitted to the LRB. The LRB will now consider the application for certification, which commences the certification process and actively involves the employer.

Time Bars

In most jurisdictions, an application for certification can be submitted to the LRB at any time. This is true in all jurisdictions if neither a certification order with another union nor a collective agreement is in effect (McQuarrie, 2015). However, certain circumstances may impose time bars or restrictions on organizing activities. These time bars might be in place if a previous certification application was denied, revoked, or cancelled and if there is an existing relationship with another union (McQuarrie, 2015). Thus, it is crucial for a group of workers to be made aware of the legislation in their specific jurisdiction.

Certification Process

Up to this point, the employer may not know that some or all of their workers seek union representation. Once the LRB receives the application for certification, the employer will be notified, and a copy of the application will be shared with them. The employer must then make information from the LRB available to all employees in the proposed bargaining unit. The list of employees who signed cards is never shared with the employer. Still, the employer must provide information on current employees and potentially their contact information so the LRB can verify that the employees who signed the cards are employed at the organization.

Most labour boards act quickly to decide on the application’s outcome to reduce the chances of employers trying to influence the employee’s decision. As noted in Figure 6.1 above, the application has three possible outcomes:

- Deny the Application — If the minimum threshold of support is not met through card signing, the LRB will deny the application for certification.

- Workplace Secret Ballot Vote — If the minimum threshold of support is met and a workplace vote is mandatory in the specific jurisdiction, the LRB will arrange for a vote in the workplace. An officer of the LRB will supervise the vote, and if 50% + 1 of the employees vote in favour of the union, the bargaining unit is certified. For example, if there are 20 employees in the proposed bargaining unit, 11 employees must vote in favour of the union being their exclusive bargaining agent.

- Automatic Certification of Bargaining Unit — In some jurisdictions, a process known as ‘card checking’ or ‘single-step certification’ may also be an option. In this circumstance, the LRB may certify the bargaining unit without a workplace vote if a certain number of cards are signed to support union representation. This option was the norm in Canada until the mid-80s when employers lobbied for mandatory voting (Ross & Savage, 2023). However, some jurisdictions still have this option. For example, in 2022, the province of British Columbia changed its Labour Relations Code to include a single-step certification process. A union will be automatically certified if 55% of employees sign cards indicating their support (King, 2024).

Labour Relations Board Hearing

When the LRB receives the application, they will consider the information provided to determine if they should grant the application. This includes the following:

- verifying that the union is a legal entity that fits the definition of union under the specific act or code

- ensuring there is sufficient support based on the threshold amount

- determining the timeliness of the application. For example, if some signatures were collected a year ago, they may not be counted

- ensuring the bargaining union is appropriate

While it is not always required, most boards schedule a hearing soon after the application for certification is submitted. This hearing allows the parties to be heard on any of the matters listed above and to raise any concerns about unfair labour practices during the certification process. If the LRB believes a representation vote will be an outcome of the application, they may conduct the vote before the hearing and seal the ballots until the application issues are resolved (British Columbia Labour Relations Board, 2024; Suffield & Gannon, 2015). Once the hearing process is complete and the board is satisfied with the application, they will either call a vote or declare the certification of the bargaining unit.

Appropriate Bargaining Unit

One issue frequently discussed during the hearing process is the appropriateness of the bargaining unit for collective bargaining. The application for certification will include a description of the bargaining unit the union wants to represent. This description is essential to the process as the labour relations board (LRB) will check signatures against an employee list and must determine whether all the employees who signed cards are in the defined bargaining unit.

The LRB must also determine if the bargaining unit description is appropriate for certification. The guiding principle to determine if a bargaining unit is appropriate is whether or not the employees included have a community of interest. According to Suffield and Gannon (2015), a community of interest “refers to the common characteristics regarding terms and conditions of work and the relationship to the employer for those in a proposed bargaining unit.”

It is also important to note that a union does not need to include all employees in the proposed bargaining unit for it to be appropriate. However, the employer and the LRB can object to the proposed bargaining unit, and all parties can argue for adjustments during the hearing process. It is also not necessary for the proposed bargaining unit to be the most appropriate, only that it satisfies the board’s definition of appropriate for collective bargaining.

According to Suffield and Gannon (2015), the following factors are relevant to defining a community of interest:

- similarity in skills, duties, and working conditions of employees [in the bargaining unit]

- structure of the employer

- integration of the employees [and their roles] involved

- location or proximity of employees

Size & Geography

The size and significance of the bargaining unit is one vital consideration, as is the physical geography of the operations. Each labour code or act will define the minimum number of positions that can be included in a bargaining unit, which in many cases is one employee. This size consideration is important for whether the union can certify the unit and whether the size is a deterrent to effective collective bargaining. A smaller proposed bargaining unit might be easier to certify for the union. For example, certifying a single store in a retail chain might be easier than doing the same for all potentially geographically dispersed stores. On the other hand, a smaller bargaining unit might make it more difficult to collectively bargain because the employer has more economic power to withstand a strike if other stores are operational.

For example, in December 2023, approximately 50 unionized Hudson’s Bay Co. workers went on strike in Kamloops, BC (Johansen & Dawson, 2023). Despite the strike occurring during the busy holiday season, it dragged on for 164 days and required a provincial mediator because the employer was unwilling to budge on their offer of a 1% wage increase during a period of very high inflation, something workers were not willing to accept (United Steelworkers, 2024). According to the United Steelworkers (2024) union, the Kamloops store is only one of two unionized Hudson Bay Co. stores in BC. The Victoria, BC store is certified under a different union and bargaining unit. In this instance, the global retailer could withstand a more extended strike, as their other stores across Canada and online remained operational. Unions need to balance the size of the bargaining unit and the implications for bargaining power against the likelihood of accomplishing the necessary threshold of support to certify. The LRB and the employer may also object to a bargaining unit that is either too large, too small, or does not make sense geographically.

Exemption of Managerial Employees

Another factor in the definition of an appropriate bargaining unit is the need to exclude any managerial employees from the bargaining unit. The rationale for this exclusion is based on the inherent conflict of interest that arises if managers are part of the same bargaining unit as the employees they oversee. One element of union democracy is that all members of a bargaining unit are at the same equal level. If a union member could have the power and authority to discipline or terminate a fellow union member, they would be in a conflict. Managers are responsible for implementing company policies and making operational decisions, and their role is to act as a proxy or representative of the employer. Including them in the bargaining unit could compromise their ability to perform these duties objectively, particularly in matters of labour relations, performance management, and hiring.

Defining who is considered a manager, however, is not always straightforward. Generally, managerial employees have the authority to make hiring, firing, promotions, or assigning work decisions. They may also have discretion over company policies and strategic direction. In some cases, the distinction between supervisory and management roles can be ambiguous, requiring careful consideration of the employee’s responsibilities and level of decision-making power. For example, a supervisor who schedules employees and directs the work of others may be able to remain in the bargaining unit, but if that supervisor is part of decision-making and strategic planning that could impact staffing levels and hiring decisions, they will likely be excluded.

According to McQuarrie (2015), the labour board will consider more than the title ‘manager’ in deciding whether a position can be included in the bargaining unit. If the answer is ‘yes’ to the first five questions below, the LRB will likely exclude the position:

- Does the person in the position have the authority to hire, fire, and discipline another person?

- Is the person in the position responsible for production or operations?

- Do people in other positions report to this position? Does this position directly supervise the work of other work performed by other positions?

- Does the person in this position have authority in a crisis or emergency?

- Does the person in this position have access to confidential information, such as employee records or budgets?

- If the person in the position does a mix of managerial and non-managerial work, how much time is spent on each?

The LRB will look beyond the title and job description to determine who can be included in the bargaining unit. In some cases, managerial employees can join a different union or form their own. Some positions may also be designated as exempt from the bargaining unit but do not fit the description of a manager and may have no authority over other employees. These might be administrative staff to senior managers, owners, or employees in the human resource management department. This exclusion can be made based on having access to information about strategic and employment decisions that would be seen as conflicting with the proposed bargaining unit.

Voluntary Union Recognition

A unique circumstance that may arise during the certification process is voluntary union recognition. For a union to be the official bargaining agent of a group of workers, it must be an organization that is not dominated or controlled by an employer (McQuarrie, 2015). Unions that are heavily influenced by employers are often referred to as company unions (McQuarrie, 2015). What results from this scenario is a collective agreement that is not in the best interest of workers but instead is one that provides concessions for employers. This type of collective agreement is referred to as a sweetheart agreement. Labour legislation makes this type of dominance by employers illegal through the certification process. It is usually identified if the employer initiates the organizing campaign and shows a desire for workers to unionize.

However, there are other scenarios where the employer might decide to recognize the union as the official bargaining agent of a group of workers without a vote or the formality of the certification process. In most jurisdictions, this is acceptable and allows the parties to submit their collective agreement to the labour relations board. An employer may recognize the union if they are satisfied that they have obtained sufficient support within an appropriate bargaining unit without undue influence and do not wish to go through the certification and voting process.

Unfair Labour Practices

While voluntary union recognition is an option in most provinces and under federal labour legislation, it is not the typical response by employers. More often, employers will resist union certification. While employers are entitled to free speech and their own opinions about unionization, communication or actions that may be seen as interfering with employees’ rights to unionize are prohibited under labour legislation. Unfair labour practices may also be perpetrated by unions, but they are most often committed by employers during the certification process (McQuarrie, 2015). At the legislation’s core is the principle that neither party (union or management) should interfere with the employee’s private decision to support unionization.

According to Suffield and Gannon (2016), the legislation protecting workers in this private decision is intended to prevent two types of employer action:

- Threatening, Intimidating, or Coercing Employees — This might include terminating or disciplining workers, promising to change working conditions if the union is not certified, or implying or stating that penalties will be applied if workers support the union.

- Interfering or Influencing the Certification Process — The employer is also prohibited from changing working conditions during the organizing campaign and certification process. This is intended to, again, prevent any influence over the employee’s final decision. Changes under this heading might include direct benefits, such as an employer suddenly offering higher wages or adding benefits. However, it might also be more subtle, such as suddenly addressing employee concerns and hiring additional staff they had previously said they would not hire.

Once the application for certification has been submitted to the LRB, labour legislation specifies that a statutory freeze is in place. This is a period of time during which employers are not allowed to change the terms and conditions of employment unless it was already planned and communicated prior to the certification process (Suffield & Gannon, 2016).

While these prohibitions might seem overly restrictive, employers also have rights during the union organizing campaign and certification process. They can communicate their views with employees, provided they do not meet the above definitions. This might include emailing employees to acknowledge that they know the certification process is ongoing and that, in their view, unionization is not in the worker’s best interest. However, employers must be cautious with statements about the union and certification as the context and audience might determine whether a communication is considered an unfair labour practice. For example, if a senior leader expresses their opinion that unionization would be bad for the company to a group of front-line part-time workers who are more vulnerable, it may be construed as threatening, while the same comment to non-management supervisor could be perceived quite differently. Employers are also allowed to prohibit entry to the workplace by union representatives and disallow solicitation on company property during work hours.

Dealing With Complaints

The labour relations board applies a standard of proof called the balance of probabilities to determine if an action or statement is an unfair labour practice. This standard differs from the standard used in criminal cases in Canada, which is beyond a reasonable doubt. It is less rigorous but requires the parties with a complaint against them to submit evidence for an adjudicator to consider and determine the probability that the action was justified (McQuarrie, 2015). For example, based on the evidence submitted, it might be reasonable that an employer terminate a known union organizer while a certification attempt is underway if the evidence shows the employee violated the company standards of conduct and a progressive discipline process was underway before the organizing campaign began. The following example from BC illustrates such a case.

Justified Action by an Employer During a Union Certification Process

In Re RMC Ready-Mix Ltd., 2021 BCLRB 99, the BC Labour Relations Board considered the termination of a long-serving supervisory employee, which the union claimed was an unfair labour practice (Kondopolus, 2021). The union argued that the employer dismissed the employee to suppress union support during an organizing campaign. However, the employer contended that the termination was for just cause due to multiple breaches of its Workplace Bullying, Harassment, and Violence Policy (RWP) and the employee’s existing disciplinary record.

Following complaints of bullying and harassment, the employer engaged an independent investigator who confirmed the allegations and recommended termination (Kondopolus, 2021). The board, considering the employee’s prior disciplinary issues and the evidence of a toxic work environment presented by ten co-workers, concluded that the dismissal was justified. Despite some union activity at the workplace, the board found no evidence that the employee’s dismissal was motivated by anti-union sentiment, thereby ruling that the termination did not constitute an unfair labour practice under the Labour Relations Code.

Read the full decision by the BC Labour Relations Board here: Re RMC Ready-Mix Ltd., 2021 BCLRB 99

Remedies

If the labour relations board determines that the employer has engaged in anti-union actions during a union organizing campaign or certification process, they will apply remedies to address the situation. The principle they use to determine an appropriate remedy is to attempt to make the situation ‘whole.’ This means they will try to reverse any harm done so that the parties can be in the same situation they were in before the unfair labour practices occurred (McQuarrie, 2015). This can be a challenge for the LRB as the effect of the violation could have already unduly influenced the employee’s private decision to choose union representation. As a result, boards have the power to apply a range of remedies to address the situation.

According to Suffield and Gannon (2016), all of the following remedies are possible in an unfair labour practices case where the employer’s action is not justified and, thus, is deemed to be motivated by anit-union animus:

- reinstatement of discharged employees

- compensation of financial loss

- interest on monies awarded

- posting or mailing of notice to employees

- access order [giving the union access to the workplace]

- freeze on working conditions

- cease and desist order

- order prohibiting future unlawful conduct

- new representation vote

- certification without a vote or remedial certification (not available in all jurisdictions)

- prosecution

The following example, again from the BC Labour Relations Board illustrates the a remedy that might be deemed to make a situation ‘whole’ under the act.

Example of Remedies Applied in an Unfair Labour Practices Complaint

The case of Gordon Food Service Canada Ltd., 2024 BCLRB 130 involved a complaint by the Teamsters Union, Local Union No. 31, alleging that the employer engaged in unfair labour practices under the BC Labour Relations Code by disciplining and terminating three employees during a union certification campaign (Phillips, 2024). The union claimed that the employer’s actions were motivated by anti-union animus, while the employer argued that the terminations were for proper cause unrelated to union activities. The union asserted that the disciplinary actions had a chilling effect on the organizing campaign and were intended to deter union support.

The BC Labour Relations Board found that the employer’s actions were tainted by anti-union animus and were conducted without proper cause, violating Sections 6(3)(a) and (b) of the Labour Relations Code (Phillips, 2024). The board ordered that the terminated employees be reinstated and made whole, which includes compensation for lost wages and benefits. Additionally, the board found that the employer had interfered with the union’s certification campaign and disrupted the organizing efforts at the worksites, further validating the union’s claims of unfair labour practices. The board also ordered the employer to cease and desist from committing further violations of the code and to post their decision in a prominent location in the workplace within seven days of the order. Finally, the employer was required to permit the union to have a 60-minute meeting with employees in the two affected locations during work time at the employer’s expense and without any management employees being present.

Read the full decision by the BC Labour Relations Board here: Gordon Food Service Canada Ltd., 2024 BCLRB 130

While it is difficult to know how much free speech an employer is permitted to exercise during an organizing campaign and certification process under a specific jurisdiction, it is clear that overt acts of anti-union animus without sufficient justification or evidence of just cause can result in immediate penalties. It is also important to note that in an unfair labour practices complaint, the burden of proof rests with the employer. For example, in the case of Gordon Food Service Canada Ltd., the union does not have the burden to prove the employer’s conduct was motivated by anti-union animus, but rather, it was up to the employer to prove that their actions were not. This reverse onus is required in most Canadian jurisdictions.

Media Attributions

- Figure 6.1 “The organizing campaign” was created by the author under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license.

References

British Columbia Labour Relations Board. (2024). The certification process. https://www.lrb.bc.ca/certification-process

Canadian Industrial Relations Board. (n.d.a). Labour relations – Certification. (2023, February 2). Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://cirb-ccri.gc.ca/en/about-appeals-applications-complaints/labour-relations-certification

Canada Industrial Relations Board. (n.d.b). Labour relations – Unfair labour practice. Retrieved February 2, 2023, from https://cirb-ccri.gc.ca/en/about-appeals-applications-complaints/labour-relations-unfair-labour-practice#toc-id-0

Gordon Food Service Canada Ltd., 2024 BCLRB 130. https://lrb.my.salesforce.com/sfc/p/#f40000022yYB/a/Mm000002Gywj/vg0cpts_SFAAKX3VbzHaz7lSenAD7koK_OS9yca1C.w

Hemingway, A. (2022, May 4). A win for BC workers: single-step union certification. Policy Note. https://www.policynote.ca/card-check/

Industrial Relations Act, R.S.N.B. c. I-4 (1973). https://laws.gnb.ca/en/tdm/cs/I-4

Johansen, N., & Dawson, J. (2023, December 10). Unionized workers at Kamloops’ Hudson’s Bay store have gone on strike. Castanet. https://www.castanetkamloops.net/news/Kamloops/461759/Unionized-workers-at-Kamloops-Hudson-s-Bay-store-have-gone-on-strike

King, A. D. K. (2024, March 18). Card-check union certification in B.C. has been aA major success. The Maple. https://www.readthemaple.com/card-check-union-certification-in-b-c-has-been-a-major-success/

Kondopolus, J. D. (2021, October 18). BC labour relations board finds no anti-union animus in discharge of 30-year employee during organizing drive. Roper Greyell. https://ropergreyell.com/resource/bc-labour-relations-board-finds-no-anti-union-animus-in-discharge-of-30-year-employee-during-organizing-drive/

Labour Act, R.S.P.E.I. c. L-1 (1988). https://www.princeedwardisland.ca/sites/default/files/legislation/l-01-labour_act.pdf

Labour Code, C.Q.L.R. c. C-27 (1996). https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/document/cs/C-27/20021002

Labour Relations Act, R.S.M. c. L10 (1987). https://web2.gov.mb.ca/laws/statutes/ccsm/l010.php?lang=en

Labour Relations Act, R.S.N.L. C. L-1 (1990). https://www.assembly.nl.ca/legislation/sr/statutes/l01.htm

Labour Relations Act, S.O. c. 1 Sched. A (1995). https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/95l01

Labour Relations Code, R.S.A. c. L-1 (2000). https://kings-printer.alberta.ca/documents/Acts/L01.pdf

Labour Relations Code, R.S.B.C. c. 244 (1996). https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96244_01

Love, J., & Warburton, M. (2021, September 17). Amazon faces Teamsters union drive at nine Canadian sites, including Nisku, Alta. CTV News. https://edmonton.ctvnews.ca/amazon-faces-teamsters-union-drive-at-nine-canadian-sites-including-nisku-alta-1.5590362

McQuarrie, F. (2015). Industrial relations in Canada (4th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Phillips, B. (2024, September 3). Fired employees of Penticton, Vernon Gordon Food Service to return to work. Peace Arch News. https://www.peacearchnews.com/news/fired-employees-of-penticton-vernon-gordon-food-service-to-return-to-work-7516761

PSAC-AFPC. (2022, May 30). Organizing for change // En avant pour le changement [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/lwj1wQTHLv8?si=ybm4kMj-UhMf1xqk

Re RMC Ready-Mix Ltd., 2021 BCLRB 99. https://lrb.my.salesforce.com/sfc/p/#f40000022yYB/a/0A0000000f8v/5IKOvgHzg8PzdBQeCS.tn2cVqs079X5WA8B9PVfKTpA

Ross, S., & Savage, L. (2023). Building a better world (4th ed.). Fernwood Publishing.

Saskatchewan Employment Act, S.S. c. S-15.1 (2013). https://pubsaskdev.blob.core.windows.net/pubsask-prod/78194/S15-1.pdf

Suffield, L., & Gannon, G. L. (2015). Labour relations (4th ed.). Pearson Canada.

Trade Union Act, R.S.N.S. c. 475 (1989). https://nslegislature.ca/sites/default/files/legc/statutes/trade%20union.pdf

United Steelworkers. (2024, January 11). Hudson’s Bay to workers: “Go on strike forever, it’s not going to change.” https://usw.ca/hudsons-bay-to-workers-go-on-strike-forever-its-not-going-to-change/

Long Descriptions

Figure 6.1 Long Description: The steps of an organizing campaign are as follows:

- A group of employees in a workplace decide to seek union representation. Employees start their own union, approach an existing union, or are approached by an existing union.

- Employees have a secret information meeting with supportive employees and union. They assess the level of support for unionization and discuss their organizing campaign.

- An organizing committee is created. It is led by one of the employees or a group of employees but also includes representatives of the union.

- The organizing campaign begins and continues until the support threshold is met. The organizing committee members collect signatures and cards from interested employees.

- When sufficient support is generated, the organizing committee submits an application for certification to the labour relations board. The application includes the description of the bargaining unit and proof of support from the employees, description of the employer, and proof of a bona fide union.

- The labour relations board considers the application with three possible outcomes

- Automatic certification (if it is an option)

- Order a workplace vote

- Deny the application

Acts that interfere with a union’s right or ability to represent its members or an employee’s right to make up their own mind about whether to support a union. Unfair labour practices also include acts by unions that interfere with an employer’s right to operate its business. (Labour Relations - Unfair Labour Practice, 2023)